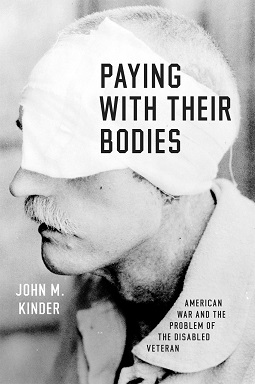

Excerpt: Paying with Their Bodies

An excerpt from Paying with Their Bodies: American War and the Problem of the Disabled Veteran by John M. Kinder

***

Thomas H. Graham

On August 30, 1862, Thomas H. Graham, an eighteen-year-old Union private from rural Michigan, was gut-shot at the Second Battle of Bull Run near Manassas Junction, Virginia. One of 10,000 Union casualties in the three-day battle, Graham had little chance of survival. Penetrating gunshot wounds to the abdomen were among the deadliest injuries of the Civil War, killing 87 percent of patients—either from the initial trauma or the inevitable infection. Quickly evacuated, he was sent by ambulance to Washington, DC, where he was admitted to Judiciary Square Hospital the next day. Physicians took great interest in Graham’s case, and over the following nine months, the young man endured numerous operations to suture his wounds. Deemed fully disabled, he was eventually discharged from service on June 6, 1863.

But Graham’s injuries never healed completely. His colon remained perforated, and he had open sinuses just above his left leg where a conoidal musket ball had entered and exited his body. As Dr. R. C. Hutton, Graham’s pension examiner, reported shortly after the Civil War’s end, “From each of these sinuses there is constantly escaping an unhealthy sanious discharge, together with the faecal contents of the bowels. Occasionally kernels of corn, apple seeds, and other indigestible articles have passed through the stomach and been ejected through these several sinuses.” Broad-shouldered and physically strong, Graham attempted to make a living as a day laborer and later as a teacher, covering his open wounds with a bandage. By the early 1870s, however, he bore “a sallow, sickly countenance” and could no longer hold a job, dress his injuries, or even stand on his own two feet. Most pitiful of all, the putrid odor from his “artificial anus” made him a social pariah. Regarding Graham’s case as “utterly hopeless,” Hutton concluded, “he would have died long ago from utter detestation of his condition, were it not for his indomitable pluck and patriotism.” Within a few months, Graham was dead, but hundreds of thousands lived on, altering the United States’ response to disabled veterans for decades to come.

Arthur Guy Empey

For American readers during World War I, no contemporary account offered a more compelling portrait of life on the Western Front than Arthur Guy Empey’s autobiography, “Over the Top,” by an American Soldier Who Went (1917). Disgusted by his own country’s refusal to enter the Great War, Empey had joined the British army in 1916, eventually serving with the Royal Fusiliers in northwestern France. Invalided out of service a year later, the former New Jersey National Guardsman became an instant celebrity, electrifying US audiences with his tales from the front lines. Despite nearly dying on several occasions, Empey looked back on his time in the trenches with profound nostalgia. “War is not a pink tea,” he reflected, “but in a worthwhile cause like ours, mud, rats, cooties, shells, wounds, or death itself, are far outweighed by the deep sense of satisfaction felt by the man who does his bit.”

Beneath the surface of Empey’s rollicking narrative, however, was a far more disturbing story. For all of the author’s giddy enthusiasm, Empey made little effort to hide the Great War’s insatiable consumption of soldier’s bodies, including his own. During a nighttime raid on a German trench, Empey was shot in the face at close range, the bullet smashing his cheekbones just below his left eye. As he staggered back toward his own lines, he discovered the body of an English soldier hanging on coil of barbed wire: “I put my hand on his head, the top of which had been blown off by a bomb. My fingers sank into the hole. I pulled my hand back full of blood and brains, then I went crazy with fear and horror and rushed along the wire until I came to our lane.” Before reaching shelter, Empey was wounded twice more in the left shoulder, the second time causing him to black out. He awoke to find himself choking on his own blood, a “big flap from the wound in my cheek . . . hanging over my mouth.” Empey spent the next thirty- six hours in no man’s land waiting for help.

As he recuperated in England, Empey’s mood swung between exhilaration and deep depression: “The wound in my face had almost healed and I was a horrible- looking sight— the left cheek twisted into a knot, the eye pulled down, and my mouth pointing in a north by northwest direction. I was very down- hearted and could imagine myself during the rest of my life being shunned by all on account of the repulsive scar.” Although reconstructive surgery did much to restore his prewar appearance, Empey never recovered entirely. Like hundreds of thousands of Americans who followed him, he was forever marked by his experiences on the Western Front.

Elsie Ferguson in “Hero Land”

In the immediate afterglow of World War I, Americans welcomed home the latest generation of wounded warriors as national heroes— men whose bodies bore the scars of Allied victory. Among the scores of prominent supporters was Elsie Ferguson, a Broadway actress and film star renowned for her maternal beauty and patrician demeanor.

During the war years, “The Aristocrat of the Silent Screen” had been an outspoken champion of the Allied effort, raising hundreds of thousands of dollars for liberty bonds through her stage performances and public rallies. After the Armistice, she regularly visited injured troops at Debarkation Hospital No. 5, one of nine makeshift convalescent facilities established in New York City in the winter of 1918. Nicknamed “Hero Land,” No. 5 was housed in the lavish, nine- story Grand Central Palace, and was temporary home to more than 3,000 sick and wounded soldiers recently returned from European battlefields.

Unlike Ferguson’s usual cohort, who reser ved their heroics for the big screen, the patients at No. 5 did not resemble matinee idols— far from it. Veterans of Château-Thierry, Belleau Wood, and the Meuse-Argonne, many of the men were prematurely aged by disease and loss of limb. Others endured constant pain, their bodies wracked with the lingering effects of shrapnel and poisonous gas.

Like most observers in the early days of the Armistice, Ferguson was optimistic about such men’s prospects for recovery. Chronicling her visits in Motion Picture Magazine, she reported that the residents of Hero Land received the finest care imaginable. Besides regular excursions to hot spots throughout the city, convalescing vets enjoyed in- house film screenings and stage shows, and the hospital storeroom (staffed by attractive Red Cross volunteers) was literally overflowing with cigarettes, chocolate bars, and “all the good things waiting to give comfort and pleasure to the men who withheld nothing in their giving to their country.” The patients themselves were upbeat to a man and, in Ferguson’s view, seemed to harbor no ill will about their injuries. Reflecting upon a young marine from Minnesota, now missing an arm and too weak to leave his bed, she echoed the sentiments of many postwar Americans: “The world loves these fighting men and a uniform is a sure passport to anything they want.”

Still, the actress cautioned her readers against expecting too much, too soon. The road to readjustment was a long one, and Ferguson warned that the United States would never be a “healed nation” until its disabled doughboys were back on their feet.

Sunday at the Hippodrome

On the afternoon of Sunday, March 24, 1919, more than 5,000 spectators crowded into New York City’s Hippodrome Theater to attend the culmination of the International Conference on Rehabilitation of the Disabled. The purpose of the conference was to foster an exchange of ideas about the rehabilitation of wounded and disabled soldiers in the wake of World War I. Earlier sessions held the week before at Carnegie Hall and the Waldorf-Astoria, had been attended primarily by specialists in the field, among them representatives from the US Army Office of the Surgeon General, the French Ministry of War, the British Ministries of Pensions and Labor, and the Canadian Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-Establishment. But the final day was meant for a different audience. Part vaudeville, part civic revival, it was organized to raise mass support for the rehabilitation movement and to honor the men whose bodies bore the scars of the Allied victory.

The afternoon’s program opened with the debut performance of the People’s Liberty Chorus, a hastily organized vocal group whose female members were dressed as Red Cross nurses and arranged in a white rectangle across the back of the theater’s massive stage. As they belted out patriotic anthems, an American flag and other patriotic symbols flashed in colored lights above their heads. Between songs, the event’s host, former New York governor Charles Evans Hughes, introduced inspirational speakers, among them publisher Douglas C. McMurtrie, the foremost advocate of soldiers’ rehabilitation in the United States. In his own address, Hughes paid homage to the men and women working to reconstruct the bodies and lives of America’s war-wounded. He also extended a warm greeting to the more than 1,000 disabled soldiers and sailors in the audience, many transported to the theater in Red Cross ambulances from nearby hospitals and convalescent centers.

The high point of the afternoon’s proceedings came near the program’s end, when a small group of disabled men took the stage. Lewis Young, a bilateral arm amputee, thrilled the onlookers by lighting a cigarette and catching a ball with tools strapped to his shoulders. Charles Bennington, a professional dancer with one leg amputated above the knee, danced the “buck and wing” on his wooden peg, kicking his prosthetic high above his head. The last to address the crowd was Charles Dowling, already something of a celebrity for triumphing over his physical impairments. At the age of fourteen, Dowling had been caught in a Minnesota blizzard. The frostbite in his extremities was so severe that he eventually lost both legs and one arm to the surgeon’s saw. Now a bank president, Republican state congressman, and married father of three, he offered a message of hope to his newly disabled comrades:

I have found that you do not need hands and feet, but you do need courage and character. You must play the game like a thoroughbred. . . . You have been handicapped by the Hun, who could not win the fight. For most of you it will prove to be God’s greatest blessing, for few begin to think until they find themselves up against a stone wall.

Dowling stood before them as living proof that with hard work and careful preparation even the most severely disabled man could achieve lasting success. Furthermore, he chided the nondisabled in the audience not to “coddle” or “spoon-feed” America’s wounded warriors: “Don’t treat these boys like babies. Treat them like what they have proved themselves to be—men.”

The Sweet Bill

On December 15, 1919, representatives of the American Legion, the United States’ largest organization of Great War veterans, gathered in Washington, DC, for the first skirmish in a decades- long campaign to expand federal benefits for disabled veterans. They had been invited by the head of the War Risk Insurance Bureau, R. G. Cholmeley-Jones, to take part in a three-day conference on reforming veterans’ legislation. Foremost on the Legionnaires’ agenda was the immediate passage of the Sweet Bill, a measure that would raise the base compensation rate for war-disabled veterans from $30 to $80 a month. Submitted by Representative Burton E. Sweet (R-IA) three months earlier, the bill had passed by a wide margin in the House but had yet to reach the Senate floor. Some members of the Senate Appropriations Committee were put off by the high cost of the legislation (upward of $80 million a year); others felt that the country had more pressing concerns—such as the fate of the League of Nations— than disabled veterans’ relief. Meanwhile, as one veteran-friendly journalist lamented, war-injured doughboys languished in a kind of legislative limbo: “Men with two or more limbs gone, both eyes shot out, virulent tuberculosis and gas cases—these are the kind of men who have suffered from congress [sic] inaction.”

After an opening day of mixed results, the Legionnaires reconvened on the Hill the following afternoon to press individual lawmakers about the urgency of the problem. That evening, leading members of Congress hosted the lobbyists at a dinner party in the Capitol basement. Before the meal began, Legionnaire H. H. Raegge, a single- leg amputee from Texas, caught a streetcar to nearby Walter Reed Hospital and returned with a group of convalescing vets. The men waited as the statesmen praised the Legionnaires’ stalwart patriotism; then Thomas W. Miller, the chairman of the Legion’s Legislative Committee, rose from his seat and introduced the evening’s surprise guests. “These men are only twenty minutes away from your Capitol, Mr. Chairman [Indiana Republican senator James Eli Watson], and twenty minutes away from your offices, Mr. Cholmeley-Jones,” Miller announced to the audience. “Every man has suffered—actually suffered—not only from his wounds, but in his spirit, which is a condition this great Nation’s Government ought to change.” Over the next three hours, the men from Walter Reed testified about the low morale of convalescing veterans, the “abuses” suffered at the hands of the hospital officials, and their relentless struggle to make ends meet. By the time it was over, according to one eye-witness, the lawmakers were reduced to tears. Within forty-eight hours, the Sweet Bill—substantially amended according to the Legion’s recommendations—sailed through the Senate, and on Christmas Eve, Woodrow Wilson signed it into law.

For the newly formed America Legion, the Sweet Bill’s passage represented more than a legislative victory. It marked the debut of the famed “Legion Lobby,” whose skillful deployment of sentimentality and hard-knuckle politics have made it one of the most influential (and feared) pressure groups in US history. No less important, the story of the Sweet Bill became one of the group’s founding myths, retold—often with new details and rhetorical flourish—at veterans’ reunions throughout the following decades.4 Its message was self- aggrandizing, but it also had an element of truth: in the face of legislative gridlock, the American Legion was the best friend a disabled veteran could have.

Forget-Me-Not Day

On the morning of Saturday, December 17, 1921, an army of high school girls, society women, and recently disabled veterans assembled for one of the largest fund- raising campaigns since the end of World War I. The group’s mission was to sell millions of handcrafted, crepe-paper forget-me-nots to be worn in remembrance of disabled veterans. Where the artificial blooms were unavailable, volunteers peddled sketches of the pale blue flowers or cardboard tags with the phrase “I Did Not Forget” printed on the front. The sales drive was the brainchild of the Disabled American Veterans of the World War (DAV), and proceeds went toward funding assorted relief programs for permanently injured doughboys. Event supporters hoped high turnout would put to rest any doubt about the nation’s appreciation of disabled veterans and their families. As governor Albert C. Ritchie told his Maryland residents on the eve of the flower drive: “Let us organize our gratitude so that in a year’s time there will not be a single disabled soldier who can point an accusing finger at us.”

Over the next decade, National Forget-Me-Not Day became a minor holiday in the United States. In 1922, patients from Washington, DC, hospitals presented a bouquet of forget- me- nots to first lady Florence Kling Harding, at the time recovering from a major illness. Her husband wore one of the little flowers pinned to his lapel, as did the entire White House staff. That same year, Broadway impresario George M. Cohan orchestrated massive Forget-Me-Not Day concerts in New York City. As bands played patriotic tunes, stage actresses worked the crowds, smiling, flirting, and raking in coins by the bucketful. According to press reports at the time, the flower sales were meant to perform a double duty for disabled vets. Pinned to a suit jacket or dress, a forget-me-not bloom provided a “visible tribute” to the bodily sacrifices of the nation’s fighting men. As the manufacture of remembrance flowers evolved into a cottage industry for indigent vets, the sales drive acquired an additional motive: to turn a “community liability” into a “community asset.”

Although press accounts of Forget-Me-Not Day reassured readers that “Americans Never Forget,” many disabled veterans remained skeptical.

From the holiday’s inception, the DAV tended to frame Forget-Me-Not Day in antagonistic terms, using the occasion to vent its frustration with the federal government, critics of veterans’ policies, and a forgetful public. Posters from the first sales drive featured an anonymous amputee on crutches, coupled with the accusation “Did you call it charity when they gave their legs, arms and eyes?” As triumphal memories of the Great War waned, moreover, Forget-Me-Not Day slogans turned increasingly hostile. “They can’t believe the nation is grateful if they are allowed to go hungry,” sneered one DAV slogan, two years before the start of the Great Depression. Another characterized the relationship between civilians and disabled vets as one of perpetual indebtedness: “You can never give them as much as they gave you.”

James M. Kirwin

On November 26, 1939, three months after the start of World War II in Europe, James M. Kirwin, pastor of the St. James Catholic Church in Port Arthur, Texas, devoted his weekly newspaper column to one of the most haunting figures of the World War era: the “basket case.” Originating as British army slang in World War I, the term referred to quadruple amputees, men so horrifically mangled in combat they had to be carried around in wicker baskets. Campfire stories about basket cases and other “living corpses” had circulated widely during the Great War’s immediate aftermath. And Kir win, a staunch isolationist fearful of US involvement in World War II, was eager to revive them as object lessons in the perils of military adventurism. “The basket case is helpless, but not useless,” the preacher explained. “He can tell us what war is. He can tell us that if the United States sends troops to Europe, your son, your brother, father, husband, or sweetheart, may also be a basket case.” In Kir win’s mind, mutilated soldiers were not heroes to be venerated; they were monstrosities, hideous reminders of why the United States should avoid overseas war- making at all costs. Facing an upsurge in pro- war sentiment, the reverend implored his readers to take the lessons of the basket case to heart: “We must not add to war’s carnage and barbarity by drenching foreign fields with American blood. . . . Looking at the basket case, we know that for civilization’s sake, we dare not, MUST NOT.”

Harold Russell

The most famous disabled veteran of the “Good War” era never saw action overseas. On June 6, 1944, Harold Russell was serving as an Army instructor at Camp Mackall, North Carolina, when a defective explosive blew off both of his hands. Sent to Walter Reed Medical Center, Russell despaired the thought of spending the rest of his days a cripple. As he recounted in his 1981 autobiography, The Best Years of My Life, “For a disabled veteran in 1944, ‘rehabilitation’ was not a realistic prospect. For all I knew, I was better off dead, and I had plenty of time to figure out if I was right.” Not long after his arrival, his mood brightened after watching Meet Charlie McGonegal, an Army documentary about a rehabilitated veteran of World War I. Inspired by McGonegal’s example—“I watched the film in awe,” he recalled—Russell went on to star in his own Army rehabilitation film, and was eventually tapped by director William Wyler to act alongside Fredric March and Dana Andrews in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), a Hollywood melodrama about three veterans attempting to pick up their lives after World War II.

Russell played Homer Parrish, a former high school quarterback turned sailor who lost his hands during an attack at sea. Much of Russell’s section of the film follows Homer’s anxieties about burdening his family—and especially his fiancée, Wilma—with his disability. In the film’s most poignant scene, Homer engages in a form of striptease, removing his articulated metal hooks and baring his naked stumps to Wilma—and, it turns out, to the largest ticket-buying audience since the release of Gone with the Wind. Even as Homer decries his own helplessness—“I’m as dependent as a baby,” he protests—Wilma tucks him into bed and pledges her everlasting love and fidelity. In the film’s finale, the young couple is married; however, there is little to suggest that Homer’s struggles are over.

Though Russell worried what disabled veterans would make of the film, The Best Years of the Our Lives was a critical and box-office smash. For his portrayal of Homer Parrish, Russell would win not one but two Academy Awards (one for Best Supporting Actor and the other for “bringing aid and comfort to disabled veterans”). He would spend the next few decades working with American Veterans (AMVETS) and other veterans’ groups to change public perceptions of disabled veterans. “Tragically, if somebody said ‘physically disabled’ in 1951,” he later observed, “too many Americans thought only of street beggars. We DAV’s were determined to change that.” In 1961, he was appointed as vice chairman of the president’s Committee on Employment of the Handicapped, succeeding to the chairman’s role three years later.

A decade before his death in 2002, Russell returned to the public spotlight when he was forced to sell one of his Oscars to pay for his wife’s medical bills.

Tammy Duckworth

At first glance, Ladda Tammy Duckworth bears little resemblance to the popular stereotype of a wounded hero. The daughter of a Thai immigrant and an ex-Marine, the “self-described girlie girl” joined the ROTC in the early 1990s. Earning a master’s degree in international affairs at George Washington University, she enlisted in the Illinois National Guard with the sole purpose of becoming a helicopter pilot, one of the few combat careers open to women at the time. Life in uniform was far from easy. Dubbed “mommy platoon leader,” she endured routine verbal abuse from her male cohort. As she recalled to reporter Adam Weinstein, the men in her unit “knew that I was hypersensitive about wanting to be one of the guys, that I wanted to be—pardon my language—a swinging dick, just like ever yone else, so they just poked. And I let them, that’s the dumb thing.” She persisted all the same, eventually coming to command more than forty troops.

On November 12, 2004, the thirty-six-year-old Duckworth was copiloting a Black Hawk helicopter in the skies above Iraq when a rocket-propelled grenade exploded just below her feet. The blast tore off her lower legs and she lost consciousness as her copilot struggled to guide the chopper to the ground. Duckworth awoke in a Baghdad field hospital, her right arm shattered and her body dangerously low on blood. Once stabilized, she followed the aerial trajectory of thousands of severely injured Iraq War soldiers— first to Germany and then on to Walter Reed Medical Center (in her words, the “amputee petting zoo”), where she became an instant celebrity and a prized photo-companion for visiting politicians.

Duckworth has since devoted her career to public service and veterans’ advocacy. Narrowly defeated in her bid for Congress in 2006, she headed the Illinois Veterans Bureau from 2006 to 2009 and later went on to serve in the Obama administration as assistant secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs. At the VA, she “boosted ser vices for homeless vets and created an Office of Online Communications, staffing it with respected militar y bloggers to help with troops’ day-to-day questions.” Yet politics was never far from her heart, and in November 2012, Duckworth defeated Tea Party incumbent Joe Walsh to become the first female disabled veteran to serve in the House of Representatives.

Balanced atop her high-tech prostheses (one colored red, white, and blue; the other, a camouflage green), Duckworth might easily be caricatured as a supercrip, a term disability scholars use to describe inspirational figures who by sheer force of will manage to “triumph” over their disabilities and achieve extraordinary success. Indeed, it’s easy to be awed by her remarkable determination, both before and after her injury. However, as just one of tens of thousands of disabled veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq, Duckworth is far less remarkable than many of us would like to believe. Nearly a century after Great War evangelists predicted the end of war-produced disability, she is a public reminder that the goal of safe, let alone disability-free, combat remains as illusive as ever.

To read more about Paying with Their Bodies, click here.