WJT Mitchell on Pixar’s The Good Dinosaur

From WJT Mitchell’s review of Pixar’s The Good Dinosaur, live at the LA Review of Books:

The Pet Collector reminds us of the most fundamental role of language: the ability to name things, and by doing so, to make them belong to us, and we to them. (The naming of and “dominion over” animals are central to Adam’s role in the Garden of Eden.) But the Collector doesn’t just take possession of his adopted family of animals; in his excessive abundance of attachments, he is clearly also possessed, and appears to be a fearful hoarder of living things. Arlo, by contrast, only needs his one companion, Spot, and he is comfortable with letting Spot go when he finds a human family to join at the conclusion of the film.

All this reeks of what anthropologists used to call totemism, the adoption of natural things (animals and plants) as kinfolk and symbols of kinship in so-called primitive cultures. The problem is that dinosaurs were unknown to primitive cultures; they are a thoroughly modern discovery, never named, classified, or adopted until the British paleontologist Richard Owen proclaimed their existence in 1843. Could it be that modern cultures need totemism too? Freud’s Totem and Taboo argued that totemism was obsolete in the modern world, while taboos still abound. But he failed to consider the possibility of a distinctively modern totemism, in which the animal counterpart and companion to the human species is an extinct family of prehistoric animals discoverable only by modern science. Dinosaurs provide the perfect Darwinian allegory for the human race — namely, the possible (or should we say highly probable) prospect that human beings could wind up just like them — extinct. That, it seems to me, is the best explanation of the strange array of contradictory attitudes toward dinosaurs as popular icons. They are friends and companions, on the one hand, and feared enemies, on the other. They are ferocious wild animals and domestic pets, vicious predators and peaceful vegetarians. In short, they are a mirror of all the varieties of our own human species, distributed across a genus of extinct animals that exist only in the realms of unbridled imagination and biological science — a perfectly modern combination.

To read the review in full at LARB, click here.

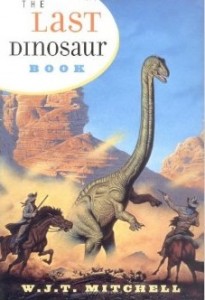

For more information about Mitchell’s The Last Dinosaur, click here.