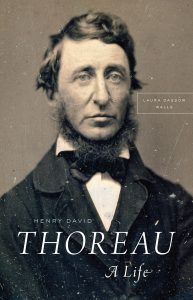

Jed Purdy on Henry David Thoreau (and our new bio!)

Laura Dassow Walls’s Henry David Thoreau: A Life (forthcoming this July) is set to be one of 2017’s blockbuster literary events: years in the making (the first Thoreau bio in a decade+) and hitting the printer at just over 600 pages, the book has already garnered pre-publication superlatives, piped up by every outlet who could get their hands on a galley, from Publishers Weekly to the Chronicles of Higher Education. And now, even the think-piece heavies are starting to weigh in—here’s an excerpt after the jump from one of our favorites, Jedediah Purdy, in his long-form piece on appreciating Thoreau, fresh off his read of Walls’s powerhouse biography, at the Nation.

***

I would bet that fewer Americans have read Walden than have heard that Thoreau’s mother did his laundry.

Yet Thoreau persists. Laura Dassow Walls, who teaches English at Notre Dame, has written an engaging, sympathetic, and subtly learned biography that makes a strong case for Thoreau’s importance; she also seems a little baffled that anyone could fail to admire him. Her Thoreau was an abolitionist who brought Frederick Douglass to speak at the Concord Lyceum—a kind of community university—and participated in the Underground Railroad, to the point of risking charges of treason by helping enslaved people flee to Canada. While living at Walden, Thoreau hosted the annual festival of the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society, where the speakers included Lewis Hayden, who had escaped slavery in Kentucky. He was deeply interested in the indigenous cultures that remained in New England, seeking out conversation and even friendship with Native Americans, studying the Wampanoag language on his own while at Harvard, and filling more than 3,000 notebook pages with material from these investigations. He also lived in a household of strong women: His sisters set the pace in antislavery activism, and Thoreau willingly took his cues from them. He even admired and sympathized with the laborers building the railroads that would clatter along the edge of his beloved pond.

The details are sometimes wonderful. On November 1, 1859, Thoreau defied the forces of law and order and the pleas of respectable friends by delivering a defense of John Brown to 2,500 people in Boston. “The reason why Frederick Douglass is not here,” he began, “is the reason why I am.” If every privilege check had that kind of snapping specificity and quiet moral thunder, they might be both more subversive and less disdained.

***

To read more about Henry David Thoreau: A Life, click here.

To read Purdy’s piece in full, click here.