How to Tame (Really Tame) a Fox

Below follows an excerpt from Lee Dugatkin’s piece on tameness at the Washington Post, which draws from his singular work of biology, How to Tame a Fox (And Build a Dog), a Cold War-driven suspense tale of scientific experimentation, Siberian winters, and one unconventional Space Race-era goal: recreating the domestication of dogs from wolves in real time, using the silver fox.

***

He and Lyudmila began to test this idea in 1959. Every year they assessed hundreds of foxes and selected only those with the most “prosocial” interactions with humans — the ones that licked people’s hands, wagged their tails and whined sadly when interactions with humans were over. These were the foxes chosen to parent the next generation.

They would then assess whether subsequent generations became tamer over time, and equally important, whether traits associated with the domestication syndrome began popping up. They did, and quickly — remarkably quickly, given the thousands of years it took for our ancestors to domesticate dogs, cows and other creatures. Within the first decade of the fox domestication experiment, the animals were not only markedly tamer, offering up their stomachs for belly rubs, but some of them had curly tails and mottled fur.

Lyudmila remembers one fox in particular from this time. In 1969, the 10th generation of foxes was born, and among them was a pup that she named Mechta, the Russian word for dream. In wild foxes, a pup’s ears are floppy until it is about two weeks old, at which point its ears take on the ramrod-straight look we tend to picture when we think of foxes. When Mechta was three weeks old, her ears had not yet straightened. They still hadn’t at four weeks, nor at five. Mechta looked exactly like a dog pup.

Lyudmila desperately wanted to show Belyaev, but he was so busy that spring that he couldn’t come to the experimental farm outside the city of Novosibirsk until Mechta was three months old. To Lyudmila’s surprise and delight, however, Mechta’s ears remained as floppy as ever when he showed up. When Belyaev saw the pup, he exclaimed, “And what kind of wonder is this?!”

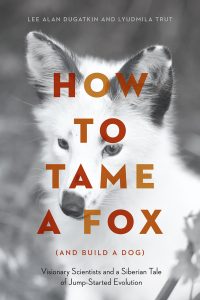

Mechta, a member of the Siberian experiment’s 10th generation of silver foxes.

By this time in the study, the domesticated foxes also had dramatically reduced stress hormone levels, indicating they were more comfortable around humans than their wild brethren, and the females had slightly longer breeding seasons. In the decades to follow, the frequency of these characteristics increased, and the foxes also developed juvenile facial features, smaller skulls and increased levels of neurotransmitters such as the “happiness chemical,” serotonin.

Belyaev was right: Select animals based on tameness and only tameness, and many of the traits that make up the domestication syndrome come along for the ride.

***

To read more at the Washington Post, click here.

To read more about How to Tame a Fox (And Build a Dog), click here.