WSJ reviews Christopher Kemp’s “The Lost Species”

Tales of expeditions to the farthest reaches of the globe by intrepid scientists and explorers in search of undiscovered species that inhabit it have always captivated the public’s imagination. Take, for example, the apparent popularity of the David Attenborough-themed raves currently taking the UK by storm, featuring episodes of Planet Earth II and Blue Planet II set to samples of the 90-year-old biologist’s narration (as well as some of today’s hottest dance tracks).

Tales of expeditions to the farthest reaches of the globe by intrepid scientists and explorers in search of undiscovered species that inhabit it have always captivated the public’s imagination. Take, for example, the apparent popularity of the David Attenborough-themed raves currently taking the UK by storm, featuring episodes of Planet Earth II and Blue Planet II set to samples of the 90-year-old biologist’s narration (as well as some of today’s hottest dance tracks).

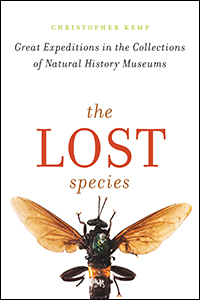

But while the BBC’s premier nature documentaries might make the work of today’s biologists seem like a neverending jungle adventure, as a recent Wall Street Journal review of Christopher Kemp’s new book The Lost Species points out, in recent years some of the most fascinating new biological discoveries were actually made by researchers working behind the scenes, sorting through vast collections of zoological specimens stored in the the drawers and cavernous basements of natural history museums.

As Kemp’s book explains, for decades after their collection, specimens housed in museum archives can remain incorrectly categorized, or not categorized at all–not only due to the sheer size of some of these collections, but also the complex detective work that must go into proper taxonomic classification. David MacNeal writes for the WSJ:

Christopher Kemp’s The Lost Species is an unexpectedly delightful and rewarding jaunt into once-cherished, now-decaying living history.

Each chapter gives a quick sketch of a species or genus that was formally described from a museum specimen, often decades after it was collected. Most of the creatures—which include lightning cockroaches, squeaker frogs, pygmy bandicoots from New Guinea, ruby seadragons and “atomic” tarantulas caught at a nuclear test site in Nevada—have been identified in the past 15 years or so.

…

There are roughly 10 million species in nature and 3 billion specimens in collections world-wide but only a meticulous few researchers to categorize them. Only 20% of the world’s species have been named, and only 18,000 new species are described per year. This book shows just how overwhelming that taxonomic workload can be.

More important, we see how confusing the classification process can get. “A species is nothing more than a hypothesis,” Mr. Kemp writes. Researchers wrongly divide animals, creating nonexistent species. Or they rediscover species already described. The samples they work from are always imperfect. A wedge-shaped beetle at the Smithsonian was disregarded for over a century and split in half before being described in 2014.

But Mr. Kemp’s colorful descriptions restore the dehydrated bits to their original vigor. A drawer of skins from the olinguito, a small arboreal raccoon, “look like a collection of bright red stoles laid side by side,” for example.

Kemp’s revelatory peak behind the scenes of natural history museums aside Blue Planet fans also needn’t worry. MacNeal continues:

[Kemp] also casts a spotlight on the bold scientists who gathered the specimens in the first place. Detective work is involved to find what scientists infer must exist. “The Lost Species” is peppered with anecdotes that remind us how dangerous chasing down uncategorized creatures can be. Mr. Kemp recounts tales of limb amputation by leopard attack, campsites tilted at 45-degree angles on a humid Ecuadorean mountain, and wooden expedition ships erupting in flames before sinking.

From the farthest reaches of the globe to the archives of some of the worlds largest repositories of zoological data The Lost Species reveals the most complete story ever told about some of today’s most groundbreaking discoveries.

Read the rest of the review on the WSJ website or find out more about the book.