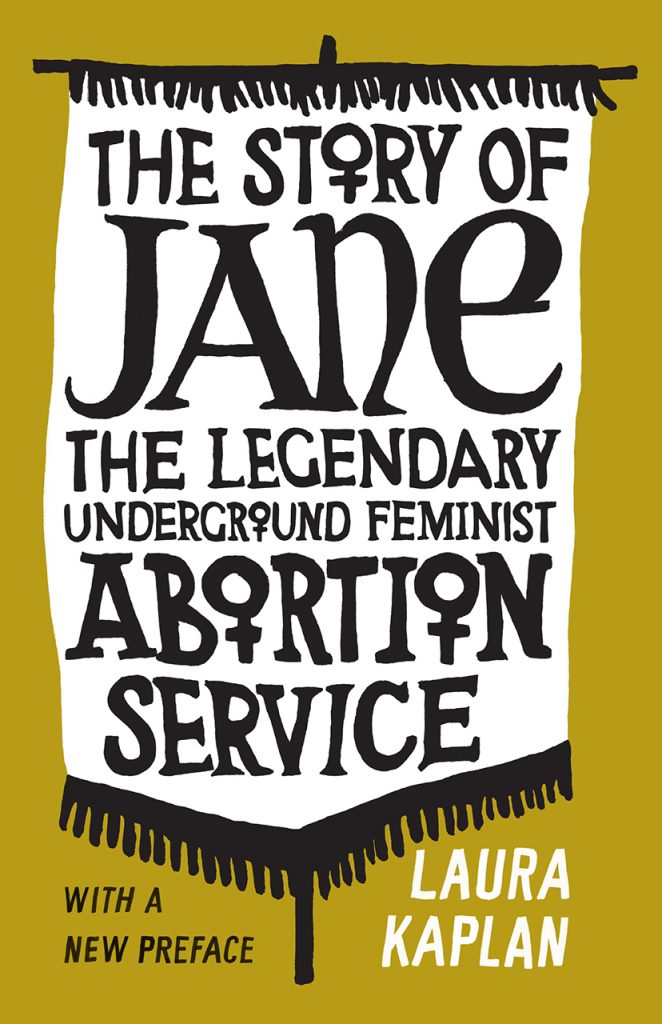

International Women’s Day—Read an Excerpt of ‘The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service’

Before abortion’s legalization, most women with unwanted pregnancies were forced to turn to illegal, unregulated, and expensive abortionists. But in Chicago, those who could discover the organization code-named “Jane” found at least some level of protection and financial help. Laura Kaplan, who joined Jane in 1971, has pieced together the histories of those who broke the law in Hyde Park to help care for thousands of women in what they called the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation. The women of Jane transformed an illegal procedure from a dangerous, sordid experience into one that was life-affirming and powerful.

First published in 1995, Kaplan’s history of Jane remains relevant today—with abortion rights once again in the crosshairs in the United States, while draconian measures already make abortions functionally inaccessible to many. Read on for an excerpt from chapter two of the new publication of Kaplan’s groundbreaking text.

Population control groups with an ominous eugenics slant joined the ranks of those lobbying for reform. They raised the specter of a dangerous global population explosion among the poor. In that view women were again, as in the medical model, the objects, not the subjects, of the abortion debate. Since their arguments supported the power of professionals to determine what was best for women, abortion was potentially a weapon used against women, rather than a tool for women’s liberation. Population control groups were attacked as genocidal by Third World activists and communities of color. The first massive trials of birth control pills were carried out on poor women in Puerto Rico and Haiti. Although hospital boards approved far fewer abortions for women of color than for white women, reports of sterilization abuses in Puerto Rico and among women of color in the United States were beginning to surface in the media. In fact, while Jenny was begging for a tubal ligation, she had heard from her contacts in the radical medical community that poor women in public hospitals in the city were being sterilized without their consent. Their women’s liberation abortion group had to reframe the arguments for abortion in terms of the control over their lives that individual women had a right to, regardless of their economic status or race.

They spent hours on the nuts and bolts of what they might do. How would they handle medical emergencies, such as a women with serious complications from an abortion? What if someone died? What would they do if one of the doctors they used was arrested, or one of them was arrested? How would they handle a police investigation? Claire cautioned them to maintain only minimal records so that, in the event of a raid, the police would find nothing incriminating. For security reasons they decided to keep their two main functions—contacts with the doctors who performed abortions, and contact with the women—separate. One group member would initially speak with each woman and put her in touch with a counselor in the group. Someone else would be responsible for contacting the doctors and arranging for her abortion. Each counselor would follow up with the women she saw. Claire had the names of a few doctors but they knew they would have to expand on that list. How were they going to find new doctors? And how would women who needed abortions find them? They joked about handing out flyers on street corners. They tried to explore every logistical question they could think of, but they knew the answers would have to come from actual experience.

Claire had learned all she knew about abortion from the doctor on Sixty-third Street. If they planned to expand the operation, they needed more information. When they researched abortion in the library, they discovered that not only was there almost nothing on abortion but there was almost no information about women’s bodies and women’s health written for lay people. What each of them knew about her body she had found out through her personal medical problems—Jenny’s Hodgkin’s disease, Karen’s fertility work. From one study of legal abortions in Sweden that they were able to locate, they learned that the basic procedure was fairly simple and, when performed by a competent practitioner, had few complications.

Since abortions in most states in the United States were illegal except to save the mother’s life, most doctors knew little about them. The group suspected the accuracy of what they read in American journals, since those were likely to be tainted by lack of experience and the authors’ biases. They realized they would have to get the information they needed from other, possibly unofficial, sources and one source was going to be women who had abortions.

They continued meeting through the spring, but now, at Claire’s direction, rather than holding philosophical discussions, they practiced counseling techniques and sat in on counseling sessions. From Claire and a few women who had been working with her, they learned to describe the abortion procedure and to answer the questions women were likely to ask. They talked about ways to deal with the various emotions, like shame and self-blame, that women expressed in counseling sessions. Along with the medical information Claire wanted them to address the political dimensions and give each woman a sense that her personal predicament was part of the larger socioeconomic-racial-sexual struggles that were going on at that time.

Throughout those months of preparation Jenny kept thinking, Just give me the names and the numbers and we’re ready to go. “Powerless, we were powerless,” Jenny says, with the same impatience she felt then. “We didn’t even have the name of a person who could do abortions. We had this strict ideological teacher who insisted on our learning our lessons before she was going to give us any telephone numbers.”

Late in the spring, they picked a name for their group: the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation. But they also needed a simpler code name. As they worried over the details of their work, Jenny said, “It looks like we’re creating a monster.” Lorraine answered, “Well, in that case, I like my monsters to have sweet names, like Fluffy or Jane.” Jane seemed a good choice. No one in the group was named Jane and Jane was an everywoman’s name—plain Jane, Jane Doe, Dick and Jane. The code name Jane would protect their identities while protecting the privacy of the women contacting them. Whenever they called a woman back or left a message for her, they could say it was Jane calling. No one else would know what the call was about. And having someone to call by name might make women more comfortable.

At the end of the training process Claire had them write a pamphlet to use for outreach and education. Jenny thought of it as their final exam. The pamphlet, “Abortion—a woman’s decision, a woman’s right,” begins with the question: What is the Abortion Counseling Service?

We are women whose ultimate goal is the liberation of women in society. One important way we are working toward that goal is by helping any woman who wants an abortion to get one as safely and cheaply as possible under existing conditions . . . .

After a few words about the Abortion Loan Fund and a section describing the abortion and follow-up, the pamphlet continues:

. . . . the current abortion laws are a symbol of the sometimes subtle, but often blatant, oppression of women in our society . . . Only a woman who is pregnant can determine whether she has enough resources—economic, physical and emotional—at a given time to bear and rear a child . . .

The same society that denies a woman the decision not to have a child refuses to provide humane alternatives for women who do have children . . . .

The same society that insists that women should and do find their basic fulfillment in motherhood will condemn the unwed mother and the fatherless child.

The same society that glamorizes women as sex objects and teaches them from early childhood to please and satisfy men views pregnancy and childbirth as punishment for her “immoral” or careless sexual activity especially if the woman is uneducated, poor or black.

Only women can bring about their own liberation. It is time for women to get together . . . to aid their sisters . . . and make the state provide free abortions as a human right . . . .

There are currently many groups lobbying for population control, legal abortion and selective sterilization. Some are trying to control some populations, prevent some births—for instance poor people and black people. We are opposed to these and to any form of genocide. We are for every woman having exactly as many children as she wants, when she wants, if she wants.

It’s time the Bill of Rights applied to women . . . . ”

Throughout the winter and spring, attendance at meetings ebbed and swelled from five to fifteen women. By late spring, when they were ready to begin the actual work of counseling and referring, the group had winnowed down to a handful of committed women.

The months of meetings had given the core group a sense of each other and a cohesiveness. They were prepared. Karen remembers their exhilaration: “This was our issue, not our men’s issue, not our kids’ school, but ours. For the first time we had something that was our own and that was exciting.”

Their last task was to divide up the work. Lorraine took the phone contact. She would be Jane; her home phone number was listed in their pamphlet. Karen continued to contact women with money to donate to the loan fund. Jenny and Miriam volunteered as the doctor contacts, the people to deal directly with the abortionists. Since the group was so small, every member, on top of her other duties, would be responsible for counseling women. For the time being they kept what they were doing word of mouth and grass roots, notifying other women’s liberation groups around the city, using their pamphlet to get their message and phone number out. Claire handed Jenny and Miriam the contact names and phone numbers for the doctors and then she was gone.

It was, in Claire’s memory, a remarkable group. She loved being with women who were going to take this problem seriously and do something about it. They were clear thinking and goal oriented and there was little of the internal bickering that Claire was finding so wearing in student and Left politics. These women seemed decent and caring, both about each other and about the women they were going to be helping. “That group of women,” Claire muses, “whether we were made that way because of the struggle and the things we had to face, or whether we were that way and therefore attracted to it, I don’t know. Jenny was so sensitive and insightful and straightforward and truth telling. You had to be both inspired and carried along by working with her. Lorraine and Karen were efficient and methodical, and Miriam, the oldest of us, with more experience in the world, brought a kind of mothering instinct to the group. No one was pretentious or b.s.”

The Story of Jane is available now! Find it on our website, online at any major booksellers, or at your local bookstore.

Laura Kaplan is a lifelong activist and a founding member of the Emma Goldman Women’s Health Center in Chicago. She is a contributor to Our Bodies, Ourselves. You can learn more about her work here.