Summer Book Club Feature: Five Questions with Jennifer Jordan, Author of “Edible Memory”

Now that the dog days of summer are truly upon us, we hope you’re staying cool lakeside or under a shady umbrella with our summer #ReadUCP Twitter book club pick, Edible Memory: The Lure of Heirloom Tomatoes and Other Forgotten Foods by Jennifer Jordan. And if you haven’t picked it up yet, it’s not too late! We’re reading throughout July and August, so there’s plenty of time for reading in-between watering your tomato and pepper plants or checking out the latest at the farmers’ market. (And there’s a handy discount code below.)

Though we’ll soon be announcing dates for our Twitter chats with Jennifer, we decided to get things started with a few questions about what inspired her interest in heirloom foods and what’s next on her plate.

Where did your interest in heirloom fruits and vegetables come from?

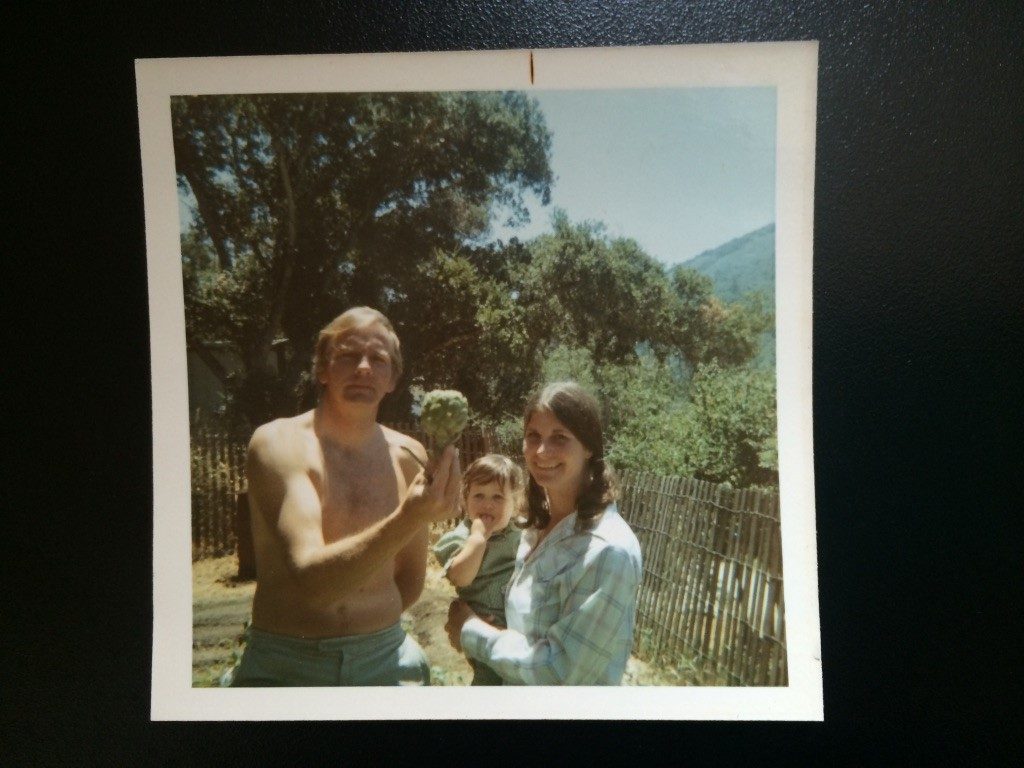

I’d say it came from two sources, one personal, one sociological. I’ll submit this photo as evidence of the personal part. I grew up in California in the 70s, and my parents (both teachers) had a cooperative garden when I was tiny. Amazingly, one of the babies I grew up with ALSO became a sociology professor! So my childhood was surrounded by apple trees and artichokes, homemade yogurt and a lot of wheat germ. Even when we no longer had that garden, and moved closer to the coast, we were always trying to grow things in the foggy summers.

The sociological interest came from the fact that I watched the rise of the heirloom tomato, and it struck me as sociologically really weird, a puzzle in need of explanation. As I ask in the book, how could something so perishable be considered an heirloom? That takes a lot of cultural work, and that’s exactly what I study—how the stories people tell each other about the past can shape the material world.

Did working on the book change the way you think about a particular food or influence your own cooking?

Immediately after I sent off the final pageproofs for the book, I felt humbled in the face of all I didn’t yet know about food, cooking, and the world in general. So the book had less of an effect on my consumption of food than it did on my consumption of knowledge. As I approach a half-century on the planet and am deep into writing my third book, the overwhelming feeling I get is of how much more there is to learn. This has happened in part through a shockingly positive experience of Twitter. I have a very curated feed (despite how many people I follow!), and I prioritize people who clearly have something to teach me. In this odd middle space of middle age, I realize how important it is to listen to elders, but also to listen to people coming up behind me in the life course—in a sense, to have mentors a generation behind and a generation ahead. Food Twitter and Beer Twitter can be highly contentious places, but they are also populated by so many wise people who are also beautiful writers and doing such vital work with food, climate, water, beer, through activism and the written word.

What are you most excited about cooking or eating this season?

Anything green and fresh. The winter in Milwaukee is very long—in ways people from elsewhere can’t understand! I mean, there were days this winter when the breweries closed because it was 30 below zero. So nothing grows, for months and months. And we had a terribly wet cold spring, where still nothing grew. You can see the effects of this in satellite images, and in the Mississippi, on a much bigger scale—acres and acres of land too wet to plant. On a much smaller scale, I got really sick in May and had to scale back all gardening (and other) ambitions as I recovered for 8 weeks, so all I could handle gardening-wise were little pots of herbs on my back porch, but that’s what I’m most excited about now. I go back and pick handfuls of chives, flat parsley, dill, curly parsley, tarragon, fennel fronds, three kinds of basil, and a huge clump of mint. No cilantro, sadly—I love it more than any other herb but I have just not mastered the art of keeping it from bolting. Some of the herbs I grew from seed, some I got as seedlings from a couple of great local nurseries and tucked them into my hand-me-down window boxes and some old terra cotta pots. Now I can have piles of fresh herbs on anything I eat.

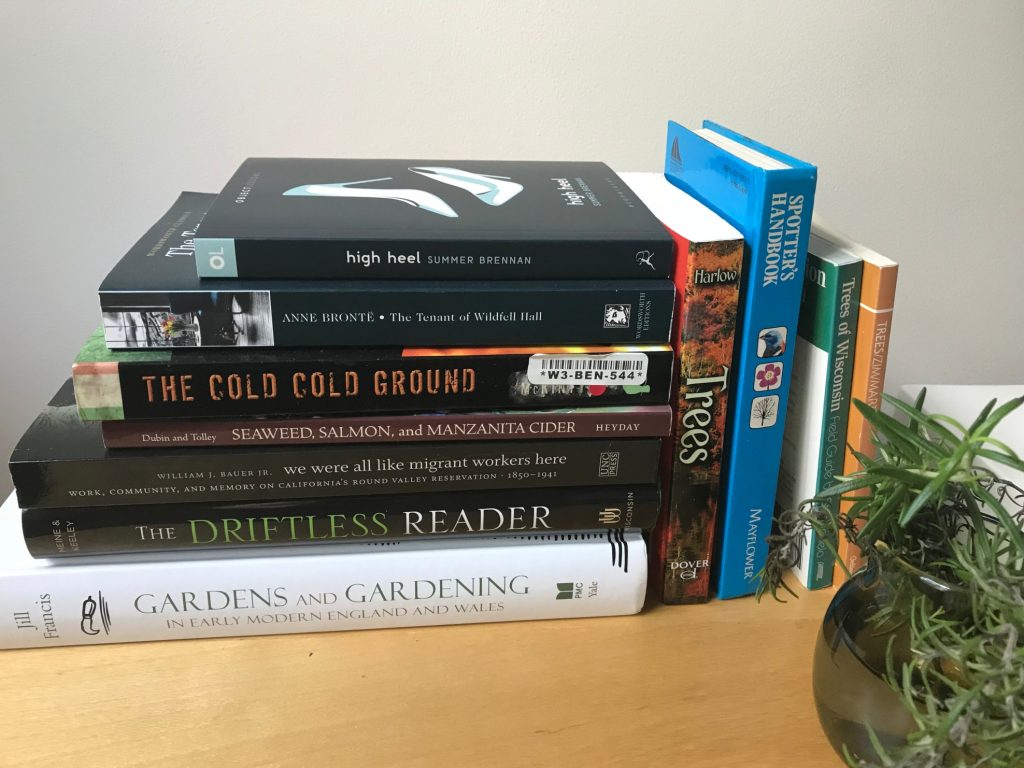

What are you reading this summer?

This may not come as a shock, but I am reading many different books without actually finishing them, and they are all over the map. Things are a little out of hand on the old nightstand, but at least I’m a fast reader. The tree books are for a class I’m taking at the Urban Ecology Center, on summer tree identification. That Harlow tree book is amazing.

What are you working on next?

Two things. I am writing a book (for University of Chicago Press!) about hops, and I am working on a collaborative research project about water and memory.

The water project sometimes intersects with the hop work. Hops like to grow in alluvial soils, so hops and creeks and rivers often have shared fates. My colleagues (Rachel Havrelock at UIC and Samer Alatout at UW Madison) and I are interested in how perceptions, conditions, and uses of the rivers of the upper Midwest changed over time, and how people are planning the futures of these rivers in the face of climate change. I focus on the historical side of things, charting the ways that people experienced these waterways in the 19th century—as sacred spaces, as sources of fish and freshwater, as carriers of cholera and typhoid fever, as places of Victorian recreation, as deeply polluted and in need of repair.

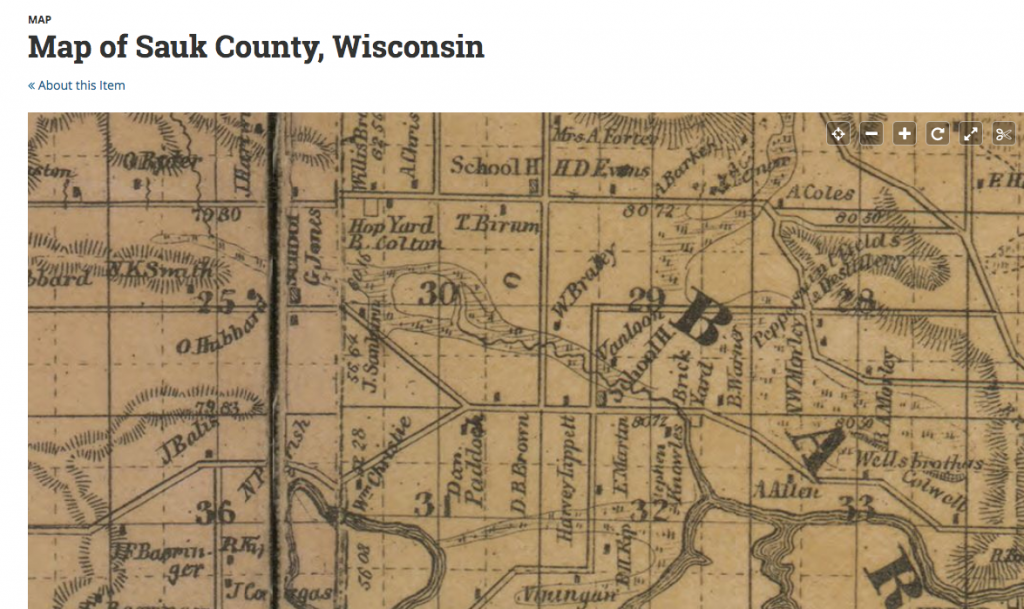

The hops book has been challenging, and often very satisfying, to research and write, and has taught me so much. I am focusing on two places that were central to 19th-century hop growing but then fell into total irrelevance—Wisconsin and California. That’s changing now, as hop growing returns to places where it once dominated, but my focus is on the rise and fall of hops in Wisconsin and California long ago. I use old property maps, 19th-century agricultural census rolls, letters, diaries, photographs, newspapers, and other archival sources to piece together the social and ecological conditions of hop growing.

One of the things that I should have known but didn’t think about until it basically hit me over the head—women are totally central to the global beer industry in the 19th century, and especially the hop industry. Most of the hop pickers in the Midwest and East were young white women, and many of the hop-pickers on the West Coast were Native American women and white women. So the global taste for beer relied on legions of women, and some men, picking the hop blossoms by hand. One of the lessons of Edible Memory is that taste shapes space—tastes for particular fruits and vegetables produce particular kinds of farms, markets, ecosystems. The same is true for beer. The taste for the bitterness and aromas that hops provide leads to particular ways of using land, and specific laborscapes as well, particular arrangements of labor and plant life to satisfy these tastes. This is a tiny piece of the bigger project.

Follow #ReadUCP and Jennifer Jordan @ediblememory on Twitter for all the latest. And go ahead and get your copy now! Use the code EDIBLECLUB for 20% from now until September through our website.