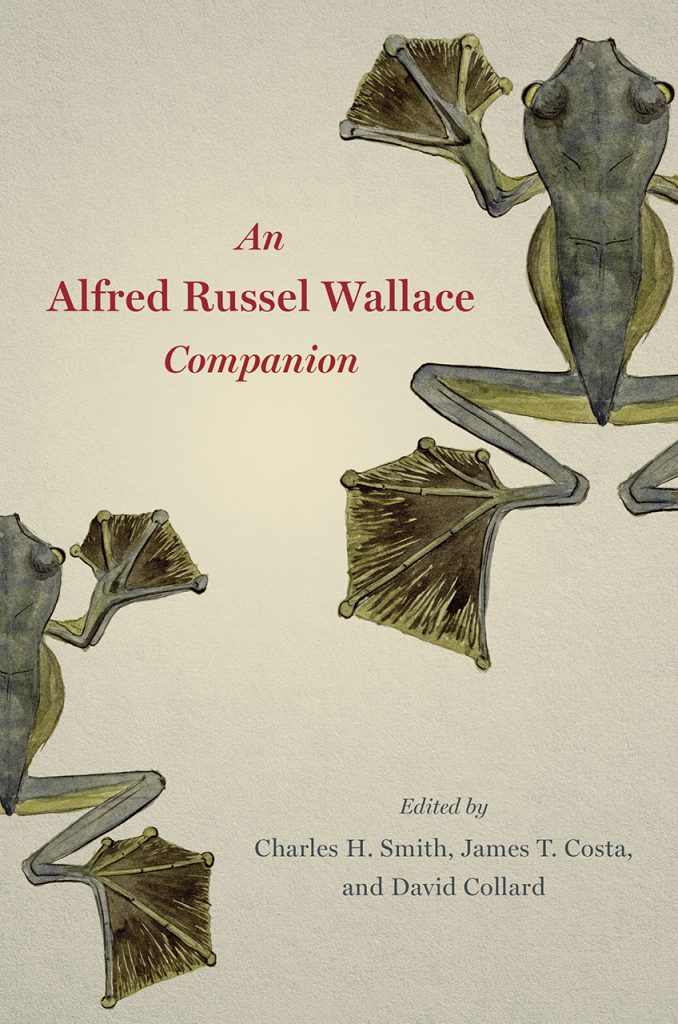

Read an Excerpt from “An Alfred Russel Wallace Companion”

Although Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) was one of the most famous scientists in the world at the time of his death at the age of ninety, today he is known to many as a kind of “almost-Darwin,” a secondary figure relegated to the footnotes of Darwin’s prodigious insights. But this diminution could hardly be less justified. Research into the life of this brilliant naturalist and social critic continues to produce new insights into his significance to history and his role in helping to shape modern thought.

Wallace declared his eight years of exploration in Southeast Asia to be “the central and controlling incident” of his life. As 2019 marks one hundred and fifty years since the publication of The Malay Archipelago, Wallace’s canonical work chronicling his epic voyage, read on for an excerpt from the editors’ introduction to An Alfred Russel Wallace Companion—a collaborative, interdisciplinary new book that celebrates Wallace’s remarkable life and diverse scholarly accomplishments.

Although Wallace’s four years in the Amazon Valley had convinced him he was on the right track as regards a causal relationship between geography and evolution, his thoughts on the mechanism of transmutation had actually not advanced much, nor did he now have collections he could study toward that end. He rested, wrote some scientific papers (and two books), and contemplated his future. Now a skilled field collector, he was able to secure a grant from the Royal Geographical Society to pay the transportation costs to his next destination, the Malay Archipelago.

Using the same basic strategy of financing his research efforts through sales of duplicate or pricey coveted specimens, Wallace was able to remain in the Far East for a full eight years. Despite frequent illnesses and travel delays, the expedition went well. Apart from an astonishing harvest of specimens, he recorded characteristics of individual plants and animals, the habits and languages of native peoples, and his impressions on the local geology and physical geography. And in 1858, halfway through the adventure, there came that communication to Darwin revealing his solution to the mechanism of evolution. A year later he sent off for publication his full description of what has become known as Wallace’s Line, a sharp discontinuity in the characteristics of geographical ranges of species in the region that became one of the important steps in the development of the modern approach to the science of biogeography. By the time he returned home in 1862, he was no longer an obscure figure toiling in obscure places for obscure reasons.

The astonishing success of Wallace’s time in the Malay Archipelago can be attributed to a number of factors, including luck: this time all or almost all of the specimens he collected actually made it back to England. But it wasn’t all luck. By paying careful attention to opportunities as they emerged, he deftly managed to visit almost all the main islands in the region. Further, one suspects that he had a real knack for dealing with native peoples: in neither the Amazon nor the Malay Archipelago did he apparently ever experience a true threat to his person, a matter for some wonder.

Although Wallace counted his twelve years in the tropics as his single most shaping experience, it is yet true that more than fifty further years of colorful events would fill his remaining days, right up to his death in 1913. For several years after his return, he concentrated on studying his collections, meanwhile attending numerous scientific meetings and doing his best to defend Darwinian tenets. In the mid-1860s he became involved with spiritualism, and by the late 1860s was beginning to publicly express concerns over some of Darwin’s positions (e.g., on sexual selection, and the origins of human consciousness). With the 1870s came explorations in a variety of subjects, including physical geography and biogeography, the theory of adaptive coloration, and, ultimately, economic and other social questions.

A steady stream of technical and popular works in these decades made his name well known across Britain and the world. His Malay Archipelago, published in 1869, was immensely popular and was succeeded by Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection (1870), The Geographical Distribution of Animals (1876), Tropical Nature and Other Essays (1878), and Island Life (1880)—all of which achieved generally rave reviews. Even his On Miracles and Modern Spiritualism (1875c) proved a hit, though appealing to a more specialized readership.

By the end of this period, Wallace was beginning to tire of the London environment and began a series of moves that would lead him and his family farther and farther into the English countryside. His financial situation, meanwhile, became something of a problem, as he had invested poorly in the 1860s and lost much of the profits from his collecting years. But he managed to keep his head above water, taking on various writing, editing, and lecturing assignments as they emerged. By the mid-1880s he had practically become an institution, having succeeded Darwin (who died in 1882) as the most famous naturalist in Britain.

An Alfred Russel Wallace Companion is available now! Find it on our website, online at any major booksellers, or at your local bookstore.

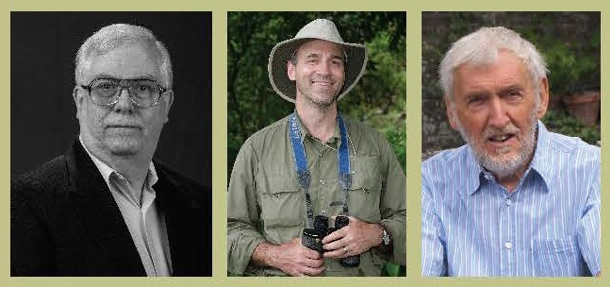

Charles H. Smith is professor emeritus at Western Kentucky University. Most recently, he is coeditor of Dear Sir: Sixty-Nine Years of Alfred Russel Wallace Letters to the Editor. James T. Costa is executive director of the Highlands Biological Station and professor of biology at Western Carolina University. Most recently, he is the author of Darwin’s Backyard: How Small Experiments Led to a Big Theory. David Collard is professor emeritus of economics at the University of Bath where he has headed up the Economics Group since 1978. He has published research on the economics of altruism, welfare, and taxation. Some of his contributions to the history of economics are collected in Generations of Economists.