Remembering David Bevington

On August 2, the Press lost a dear friend and author, David Bevington (1931–2019). David was not only a preeminent Shakespeare scholar at the University of Chicago and the author of such books as This Wide and Universal Theater: Shakespeare in Performance, Then and Now, but he, along with his wife Peggy, was a generous supporter of the Press and its authors through the Bevington Fund. In memory of David, Press Editorial Director Alan Thomas offered this tribute.

David Bevington’s influence as an editor and interpreter of medieval and Renaissance literature is plain to see: his Bantam paperback editions of Shakespeare’s plays are classroom favorites, and several of his scholarly books have become critical classics. But the fond reminiscences that filled social media after David’s death highlighted a different theme: his extraordinary generosity toward younger scholars. He continued to attend conferences and campus talks well past his retirement, following the work of the latest generation and dispensing encouragement.

In 2006, David and his wife Peggy, who for three decades had been a teacher at the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, offered the University of Chicago Press a $100,000 gift to support the publication of authors’ first books. David recalled that Harvard University Press had published one of his early books with the help of a similar fund established by a retired professor. “It struck me as such a wonderful thing, I was eager to do the same,” he said. “I really think the University of Chicago Press is the premier academic press in the United States, and so to contribute to that is a joy. It is supporting the scholarly mission right at the heart of the University.”

Augmented since 2006 by additional gifts from the Bevingtons and their former students, the fund has supported over 50 scholarly books in fields from literary studies to anthropology, history, and urban studies. It has also helped inspire other focused publication funds at the Press, including an endowment established in honor of Neil Harris, emeritus professor of history the University of Chicago, to support illustrated books of history.

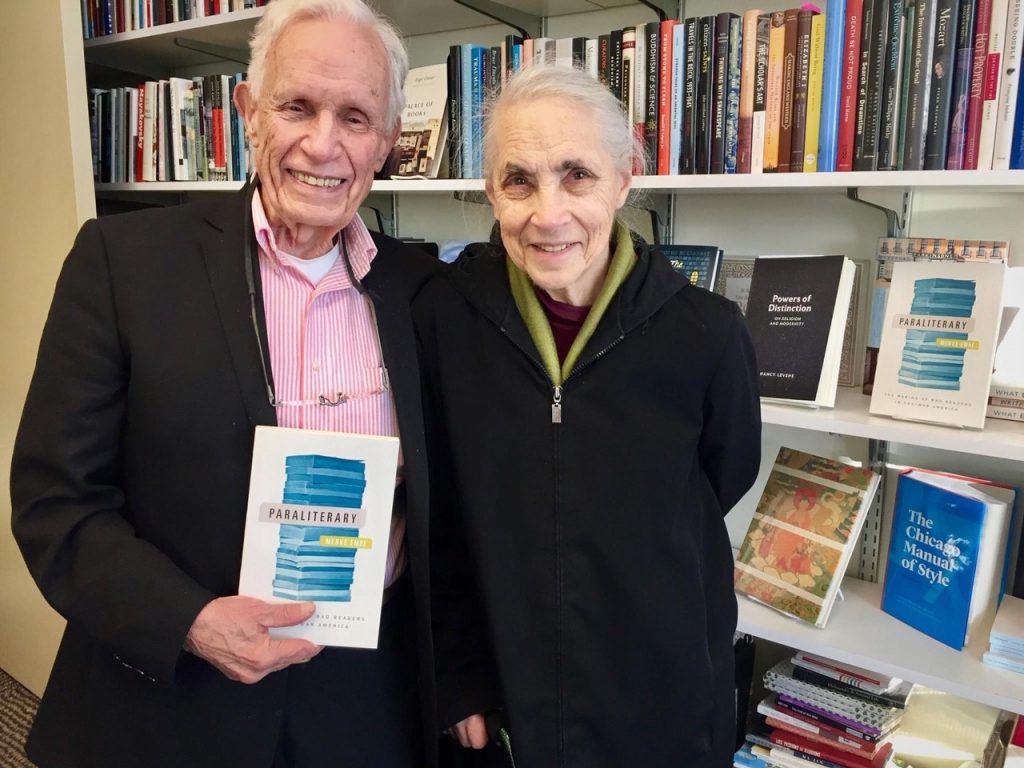

Among the books supported by the Bevington Fund is Merve Emre’s Paraliterary: The Making of Bad Readers in Postwar America (2017). “I think about David and Peggy Bevington’s generosity almost every time I sit down to write,” says Emre, now associate professor of English at Oxford University and fellow of Worcester College. “At a time when it is increasingly difficult for university presses to publish specialized scholarly research, let alone books by first-time authors, it was immensely heartening to learn that there were people like David and Peggy willing and eager to support the work of young critics.”

Sources like the Bevington Fund have become vital to the Press’s ability to publish scholarly monographs in reasonably priced print and electronic editions. Publication costs for such books—from acquisition and peer review through copyediting, design, production, and marketing—are partially recovered by sales to individuals and libraries. The balance is covered by subsidies, whether indirect—such as sales of the Press’s more popular books—or direct, such as subventions from the author’s institution and support by endowments such as the Bevington Fund. Endowment funds are especially important in helping to publish books by the growing proportion of contingent faculty, who seldom have recourse to institutional subventions.

UChicago associate professor of English Ellen Mackay, whose Persecution, Plague, and Fire (2011) was also supported by the Bevington Fund, recalls David Bevington as “a remarkable scholar . . . but also unflagging and genuinely enthusiastic in his support of new projects, arguments, methods—he nurtured even their tenderest shoots. I will remember him as a model of what academia can and should be.” At a time when questions about what academia can and should be are asked with new urgency, David and Peggy Bevington’s legacy to the Press is both an example and a beacon.