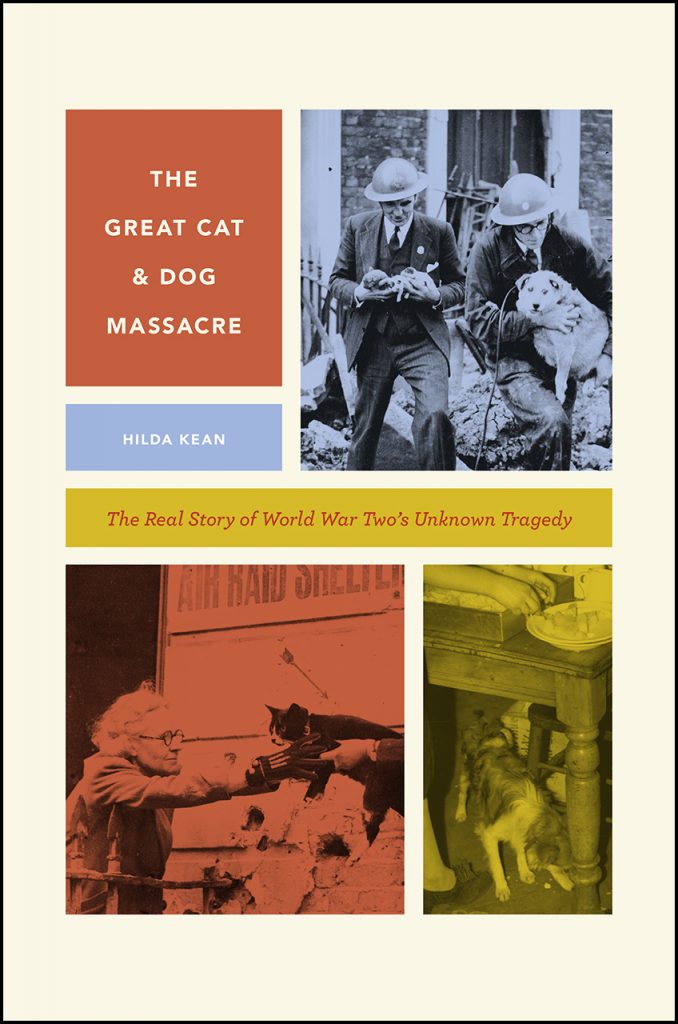

Everybody at a Time like This Should Keep Animals: Read an Excerpt from “The Great Cat and Dog Massacre”

During these strange quarantine months, many of us have been seeking comfort in our animal friends, who have been our companions in isolation and our sense of hope and distraction. In this excerpt from The Great Cat and Dog Massacre: The Real Story of World War II’s Unknown Tragedy, Hilda Kean looks at a time during the War when we similarly marveled at our pets’ remove from the larger events of the world.

In a letter penned in March 1940, the English author, journalist, and criminologist Fryniwyd Tennyson Jesse attempted to explain the mood of wartime London to American friends by incorporating her two cats into the narrative:

I watch [our cats] with a sense of relaxation and pleasure because they know nothing about war. I think everybody at a time like this should keep animals, just as royalties and dictators should always keep animals. For animals know nothing of politics, nothing of royalty, nothing of war unless, poor creatures, they also, knowing not why, are wounded and killed.

By situating animals as apart from (human) politics, albeit included in the suffering of war that embraced animal and human alike, Tennyson Jesse suggested that animals conveyed a particular quality needed in warfare: “This quality of something untouched by the social, snobbish and more serious matters that torture us, is what animals give us, and as a contribution to civilisation, believe me it is of inestimable value: it has become our only rest-cure.”

For example, near the beginning of the war when animals and humans alike were getting acclimatized to the new sounds of warfare, including air raid sirens, Gwladys Cox—a middle-age woman who lived in West Hampstead with her husband, Ralph, and her tabby cat, Bob—wrote about the new routines: turning gas off at the mains, grabbing gas masks, and catching Bob and putting him in his basket. When she writes of Bob, “he must think us mad, such goings-on in the middle of the night,” I am not sure we are meant to read this literally. Rather this is a way of showing that prewar routines of the cat as well as those of Gwladys and Ralph were disrupted: Time itself was being almost overturned by warfare.

Relationship implies a reciprocal process. One middle-aged woman explained to Mass Observation interviewers that she had obtained her own small dog after the start of the war, precisely to create domestic companionship for herself: “I’ve been all alone in the house since my husband went and the children were evacuated—and that dog’s been wonderful company.” The strength of the cross-species companionship was also evidenced by the account of a middle-aged working class man who confidently attested about his mongrel’s behavior: “If I ever go out and leave him, he always sits by my chair never stirs or anything, won’t eat or even take a drink not until I come in, then he’s as lively as anything . . . they’re good companions, better than human beings I think!” Animal-human relationships focused on comfort, support, and companionship were often recounted in the wartime Mass Observation surveys of interviews with individuals with—or without—dogs. One man interviewed by Mass Observation in Euston, having noted that his dog didn’t like air raids, explained it thus: “Yes he whines a bit but we all have to put up with something.” Here, one imagines, the man is also a being who “whines a bit.” Certainly, albeit in an understated way, the strength of the bond is one that is seen to endure despite difficulties. This is emphasized by the use of the conditional mood: “Yes he minds [the raids] a hell of a lot he mopes for days after, he was terrible during last September. I thought I’d have to have him destroyed, because you can’t find homes for dogs these days” (my emphasis).

Another man explained a similar dilemma, “I think I’d have a dog put to sleep unless I knew he was going to a very good home where he’d be happy” (my emphasis). In such instances the killing of a canine companion has not taken place: Despite the stress of raids this was an unlikely action for the men to have contemplated, as their use of language confirmed.

One young man whose mongrel dog had died some six months previously situated the domestic relationship within the broader context of the mood of the nation. When asked, “How do you feel about people keeping dogs nowadays?” He replied “I take my hat off to ’em.” Although he acknowledged that dogs “are unpopular nowadays” and that people had been “downright rude” to him about keeping his dog, the young man expanded:

It’s foolish really. Probably dogs do more to uphold morale among their owners than anything else. And dogs are doing their bit in the war too. Dog messengers at the front always have done a lot of good in wartime. Surely they’ve earned the privilege of being allowed to live for all their kind—even if it has to include the duchess’s spoilt peke feeding on tongue, chicken, cream and orange juice [sic].

This account is interesting on different levels. Here “the war” is seen as something happening “somewhere else,” the Home Front is not part of the “war.” The actions of certain dogs “at the front” are seen to give value to the species as a whole. Dogs have a positive effect on humans (“morale”) with whom they live—albeit not generally. The class divisions that still sharply existed during the war are seen, however, not to override a “commonality” of the dog species. When subsequently asked if he thought the government approved of dog-keeping or not, the interviewee retorted: “It certainly does not—but then like all things they haven’t given it much thought and won’t give it any thought till they’ve killed every dog in the country and wonder what’s gone wrong.”Thus the government’s perceived stance towards dogs became an exemplum of general incompetence. The dogs may have maintained morale but this was undertaken, he argued, in the face of state neglect of humans and animals alike.

The Great Cat and Dog Massacre is available from our website and your favorite bookseller.