Read an Excerpt from “Crusade for Justice” by Ida B. Wells, Born on This Day in 1862

Today marks the 158th birthday of journalist, activist, and civil rights icon Ida B. Wells-Barnett, born into slavery in Missouri on July 16, 1862. Wells, posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize earlier this year for her “outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching,” left a legacy that endures today alongside the continued fight for racial justice. Nearly a century after her death, her work, rather than echoing the past, holds a mirror to contemporary society. She continues to teach us about the hard work of social change and the long road that still lies ahead.

As Eve L. Ewing writes in the foreword: “Generations after the passing of Ida B. Wells, her battle continues. We still fight in defense of Black people’s basic humanity, our right to a fair application of the laws of the land, and our right to not be brutally murdered in public. In light of this continued struggle, maybe we don’t need more moving oratory or another inspirational fable about mythological people. Maybe we just need the whole truth.”

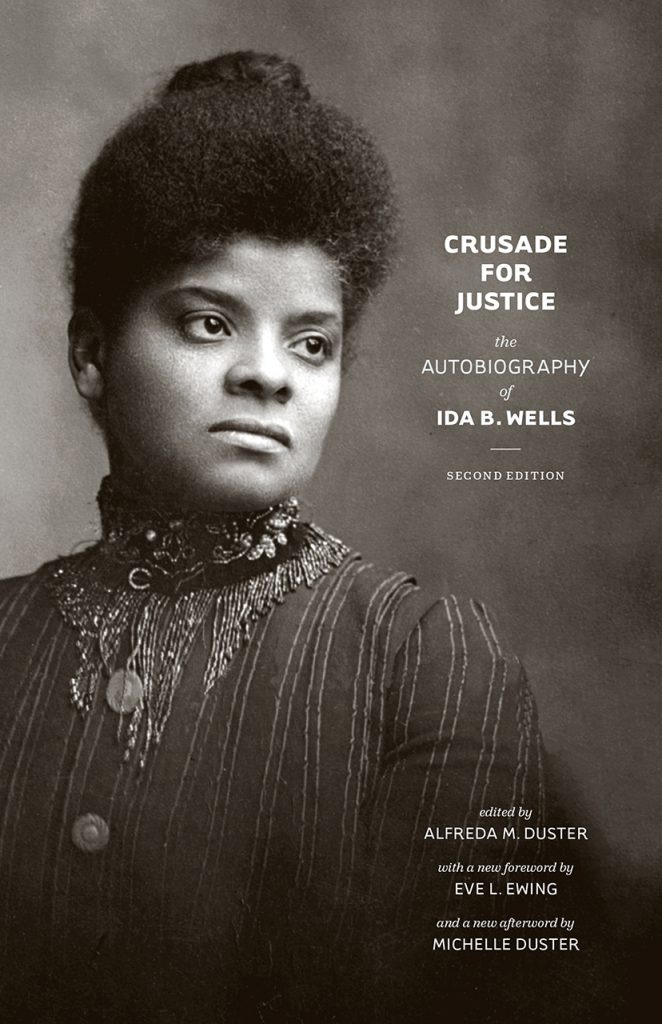

Today, in celebration of her birthday, we offer “The Tide of Hatred,” an excerpt from Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells, edited by Alfreda M. Duster.

On Sunday, 29 July 1919, the city of Chicago was startled to hear that a colored boy who had been bathing at the Thirty-first Street beach had been pelted by white hoodlums while he was in the water until he was drowned. It was charged that the policemen had refused to arrest the white boys who were responsible and a small riot broke out. That account, very highly colored, appeared in the Monday morning papers. After reading the same, Mr. N. S. Taylor, who was president of the Equal Rights League, and I went to the ministers’ meeting and urged that some action be taken by that body.

At Quinn Chapel we found the Methodist ministers discussing the situation. A message came inviting them to Olivet Baptist Church, where the Baptist ministers were in session, and it was accepted. When we reached the church at Twenty-seventh and Dearborn, we went into a committee of the whole for the purpose of forming a permanent organization. This organization met daily while the trouble was in progress, and a committee was appointed to wait on Mayor Thompson and the chief of police asking protection for our people.

Next day the streetcar strike was on, which made it harder still to get about. Down in the second and third wards (the black belt) there was very little rioting; but the outlying districts sent almost hourly reports of outbreaks and attacks being made upon our people. A “Hindenberg line” was formed by colored men east of State Street to repel the hoodlums over in the Stockyards district, who were reported to be coming over to annihilate Negro citizens, and the police stations were jammed with those arrested by the police.

A grand jury was impaneled, and Mr. Maclay Hoyne, our state’s attorney, promised to see that punishment was meted out to the rioters. Mr. Edward J. Brundage, attorney general for the state of Illinois, came into the city and offered to assist in the prosecution of the rioters.

The reporters of the daily press asked interviews and published what I said about the riot. Among other things, I said that the colored people did not want Mr. Brundage to take charge; that we had a state’s attorney perfectly capable of doing the work, and that he should do it so there would be no passing of the buck. We did not want Mr. Brundage to do here what he had done in East Saint Louis, where after months of trial only five white persons were in the penitentiary for that outrage and fifteen colored men had been sentenced for years for protecting themselves from attacks by the white rioters.

The historian of the future will wonder why the grand jury invited me, among others, to come over and testify. I had seen no deeds of violence, although I had been out on the streets every day, but I offered to present dozens of persons who had brought me stories of their mistreatment. This I did. Some who were afraid to go to the criminal courts building came to my home after dark and told their stories to members of the grand jury who came out to hear them.

After that testimony, they were sent down to Mr. Hoyne’s office to give names and addresses of persons in the mob they had recognized to the chief investigator.

We never found that Mr. Hoyne ever confronted these people with the defendants and the grand jury refused to indict any more colored people because they were not the instigators. A letter in protest was sent to the papers asking for Mr. Hoyne’s removal from a consideration of the riot cases and demanding that a special state’s attorney be employed. The grand jury had already “struck” because Mr. Hoyne only brought before them colored men. They said that colored men couldn’t have created a riot by themselves and refused to hear other cases until some white men were brought in. We also asked that this same grand jury be continued for another month so that it might complete its work.

Our Protective Association, which had been meeting daily at the New Olivet Baptist Church, took up the consideration of the suggestions in my letter. A motion was passed at the meeting following the printing of that letter to appoint a committee of seven to wait upon Attorney General Brundage and ask him to take charge of the proposed continued investigation. This after my protest in the daily papers had prevented his appointment previously! I pleaded with the men not to send this committee; that if they had no regard for my position in the matter I urged them to think about the 15 colored men that Brundage had put in prison after the East Saint Louis riot, and the 150 killed. But led by Rev. L. K. Williams, the motion prevailed to send this committee to Brundage, and Rev. Williams was made chairman.

I then rose and laid my membership card on the table and told the men that I would not be guilty of belonging to an organization that would do such a treacherous thing as to ask the white man who had put fifteen of our people in prison to take hold and do the same sort of thing here. Rev. Williams said, “Anyhow he is a Republican and he would be better for us than Hoyne, who is a Democrat.” As I passed out of the room, Rev. Williams said, “Good-bye,” and Rev. Branham said, “Good riddance.”

I walked down South Parkway with tears streaming down my face, thinking of those so-called representative Negroes asking that man to do to us what he had already done in East Saint Louis. It seemed like approval of the fact that he had already put in the penitentiary fifteen Negro men and they wanted to give him a chance to put more in. I never went back to a meeting of the so-called Protective Association, and very soon it became a thing of the past.

Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) was an African American journalist, newspaper editor, and abolitionist. Alfreda M. Duster (1904–1983), daughter of Ida B. Wells, was a social worker, mother, and civic leader in Chicago.

Crusade for Justice is available from our website or your favorite bookseller.