Ten Things I’ve Learned Designing for a University Press

We’re often introduced to a book through its cover. Catching our eye on a bookstore display, in a social media post, or shared by a favorite reviewer, covers give us a glimpse into what each book holds. But how does a cover come into existence? What goes into the process and how do designers dream them up? We checked in with Natalie Sowa, one of our very own in-house designers, to hear about working in book design. In turn, she offers the ten things she’s learned while designing covers for a university press.

1. A book cover is an overture.

A cover cannot possibly contain everything in the book; its function is entirely different. An overture is a broad musical interpretation of a larger work of music; it picks themes and snippets from the work and puts them on display to whet the aural appetite. This is the function of a good book cover. The book is the entire musical composition, complete and exhaustive. The cover hints at what is inside and entices readers to open it. The best covers often focus on a single idea and visualize it in a way that’s difficult for potential readers to ignore.

2. It is good to make it with your hands.

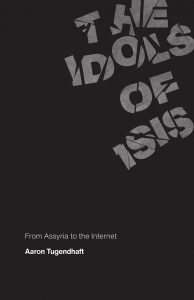

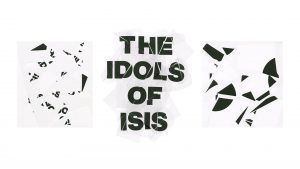

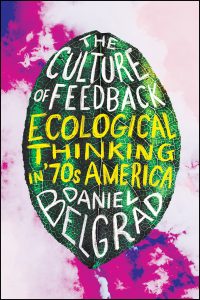

There’s something magical in letting gravity influence your design. Imperfections from producing something in an analog space are almost always more interesting than digital perfection. For my cover of Tugendhaft’s The Idols of ISIS I printed out the type, turned the page upside down, and blindly sliced it with a scalpel. Then I kept it upside down and scanned it on a flatbed scanner, leaving the cuts and initial position of the letters to chance. While I still spent days tweaking and adjusting the scans digitally for the final cover, the initial cover owes a lot to the way in which I physically manipulated the type. It’s also my preference to hand draw type when it’s appropriate, as in the scrawly, psychedelic protest poster inspired The Culture of Feedback (Daniel Belgrad).

3. Book cover design is a collaborative process.

There’s a popular misconception that book designers create alone in a dark room and emerge, triumphant, with a fully formed book cover clutched in their raised fist. While I doubt any designer does this, book design is an especially collaborative beast. The content has come from an author (or authors) who’ve spent years and sometimes decades writing it. The marketing plan positions the book to actually sell copies and considers existing visual vernacular when evaluating a book cover design. Art direction considers the efficacy of a cover’s communication outside of the designer’s own head and offers feedback to strengthen it or get the cover to fit better in a certain niche. For me, cover design is a conversation from the moment I’m assigned a project. Even looking at my thumbnail sketches, I consider these different perspectives as I make decisions.

4. Your darlings must die.

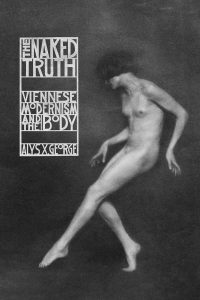

I’ll get this out of the way right now: as a designer, I don’t have a favorite color. I don’t have a favorite font. I’ve got a toolkit that I deploy for each project. I use what’s appropriate for the content of the book and the context of the book’s marketing plan. In the end, a design should justify itself as the best option. I can’t say: “I used this font because it’s elegant and I think about it when I fall asleep at night.” I can say: “this lettering was developed to evoke the Wiener Werkstätte’s experimental modern designs, concurrent with the Bauhaus and Art Deco.”

5. Cover design is a marathon, not a sprint.

I often have no idea what a final cover will look like when I begin designing it. A pet concept might look terrible when I really flesh it out and draw it to scale. My strategy is to sit with a cover and an idea for weeks. I develop it, first as tiny thumbnail sketches that include every possible variation, then as refined digital sketches where color isn’t considered (I print drafts out on a laser printer in black and white; if the cover doesn’t work in greyscale, then it won’t work in color) then as full-color digital sketches. Often, I’ll circle back around to physical pencil sketches again.

6. The unconscious does some of the work.

At the risk of sounding too Jungian, I’m unconsciously thinking about cover designs every day. Active thought and inactive thought factor into my most successful designs; sometimes I’ll spend an entire day working on tweaking a cover design, then feel myself hitting a wall. I’ll go make dinner. I’ll play a game of catch with my cat. The next morning, I may do more rote design work, or work on a different project altogether. I have learned to build in this time into the cover design process, because it’s usually only afterward that I return to the project and know how to fix and complete a design.

7. Good art direction begins with the author’s brief.

Art direction is, briefly, the concepts and parameters within which a project is designed. It’s like advice, except that it’s usually better taken than ignored. The best art direction I’ve received from an author told me, in general terms, what things to avoid: “don’t use this visual metaphor and don’t have this sort of look, because the book isn’t about that. You might consider this metaphor instead . . .” These are valid parameters that help me design something appropriate to the book and save me a lot of time that could be wasted exploring the wrong ideas. Subjective advice such as “I don’t like this color, can we change it?” isn’t helpful in crafting effective visual communication for a book.

8. A design approach is often determined by the letters in a title.

For the upcoming An Unnatural Attitude, after typesetting numerous drafts, I did the lettering by hand. It’s inspired by art deco lettering from the Weimar period, but has a more graceful, natural style to it with the linked letters and alternate “A”s, causing the duplications to seem a bit less jarring than if they’d been set in a serif or a script.

9. Doing other things makes you a better designer.

When I’m not designing books, I bake bread. I read about 17th-century ecologies and domestic histories. I follow theatrical, narrative photographers (@everydayruralamerica, Gregory Crewdson, Ren Hang, John Bulmer) that create cinematographic images. One of my recent book covers for The University of Chicago Press, Puritan Spirits in the Abolitionist Imagination, put these disparate interests to use (well, all but the bread baking). It was inspired by an atmospheric photo from Fabrizio Conti. As I was reading the manuscript, it occurred to me that Gradert’s overlapping histories meant that the physical settings of these two time periods may have looked similar; people in the 1600s could have seen a similar landscape to those who lived in the 1800s. I found a photo that seemed both cinematic and chronologically ambiguous and overlaid the title in type that was taken from publications of Cotton Mather’s Puritan sermons. The translucent, neon-esque red was just jarring and unnatural enough to touch on the ghosts that Gradert evokes in the book. One of my colleagues in marketing said that the final cover looked like a poster for the Puritan horror film “The VVitch” and that was a fantastic compliment.

10. Academic publishing rewards curiosity.

In my two years at the Press, I’ve worked on books about wild parrots, the Third Reich, the Chicago Seven, the future of democracy, ethnomusicology, the relationship between horses and humans in art, and cellular suicide. The breadth of subjects for which I’ve designed is vast, and it’s one of the special perks of designing books at a university press. I’m also able to cultivate interests in particular subjects: Wittgenstein, for example. I’ve been fortunate to develop a few different visual vernaculars for Ludwig (he’s one of my favorite critical thinkers), specializing in visualizing some of his more abstract ideas.

Natalie Sowa is a book designer educated in England and the United States and has been with the Design Department at the University of Chicago Press since 2018.