Read an Excerpt from our #ReadUCP Book Club Pick, “Picturing Political Power”

Our #ReadUCP Twitter Book Club Pick for fall is Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement by Allison K. Lange. For as long as women have battled for equitable political representation in America, those battles have been defined by images—whether illustrations, engravings, photographs, or colorful chromolithograph posters. They have drawn upon prevailing cultural ideas of women’s perceived roles and abilities and often have been circulated with pointedly political objectives. Picturing Political Power offers perhaps the most comprehensive analysis yet of the connection between images, gender, and power. In this examination of the fights that led to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, Lange explores how suffragists pioneered one of the first extensive visual campaigns in modern American history.

Below is a brief excerpt from the book, and since we’ll know you’ll want to read more, you can use the code READUCP to buy the book from our website for 30% off. Then, mark your calendars to join our Twitter Book Club Meet-up with the author for a Q & A on October 26 at 2:00 PM CT. Just follow the hashtag #ReadUCP.

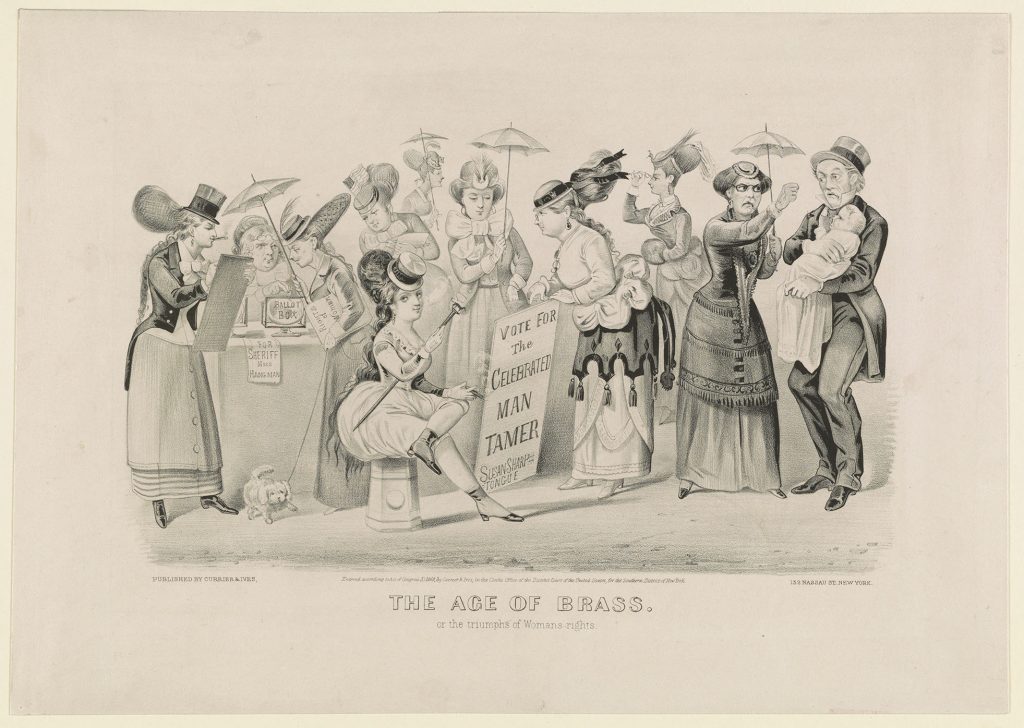

In 1869, Currier & Ives, the era’s most famous printmaker, published The Age of Brass, or The Triumphs of Woman’s Rights to depict what would happen if women won equality. This print depicts a group of elite white women as they gather to cast their ballots. Some wear enormous bows around their necks and towering, unwieldy hairstyles. To wear such absurd feminine fashions, the picture implies, they must be irrational and ignorant of important issues. Other women in the image have a masculine aesthetic—top hats, bloomers, morning jackets—to prompt laughter from viewers at their cross-dressing antics. On the right, an angry woman, whose glasses signal her education, scolds her shocked husband, the only man in sight. To viewers used to idealized images of women, she would have appeared ugly. Instead of caring for her family, as she should according to the day’s social norms, the woman abandons her baby with her husband in order to engage in politics. To reiterate that women’s rights would lead to the submission of men, a sandwich board advises women to cast their ballots for “Susan Sharp Tongue,” the “celebrated man tamer.”

Cartoons like this one dominated popular representations of political women throughout the nineteenth century. According to opponents, if women won rights, they would disdain family life and transform American society. Adversaries of women’s votes believed that men already represented the interests of their families. This print, and the many others that came before and after it, depicted female voters as a joke. Women had gained property rights and greater access to education by 1869, but surely they would never win the vote. Currier & Ives sold the print to audiences who wanted to laugh at their fears and at these reformers.

Female voters may seem unremarkable today, but the majority of Americans—men and women alike—vehemently opposed them for most of the nation’s history. The Currier & Ives print illustrates the real anxiety that many felt about changes to voting rights. When this print was published in 1869, Americans were deciding who would have political power after the Civil War. Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment to grant the ballot to black men. Many Americans wondered: If formerly enslaved men could vote, who was next? That same year, the territory of Wyoming granted women the ballot. Reformers also established the first national organizations to advocate for women’s suffrage, the right to vote, throughout the United States.

From the colonial era through the present, satirical images consistently represented political women as power-hungry, masculine-looking activists who deserted their families to pursue fame and end traditional family values. Pictures that circulated publicly often portrayed elite white men as powerful, revered leaders, but comparable imagery of women and people of color barely existed. Nevertheless, reformers persisted. While opponents relied on old tropes, suffragists coordinated the first visual campaigns to transform notions of political womanhood. Visual politics—the strategic use of images to promote a cause or candidate— proved central to their efforts to change Americans’ expectations for political women. Suffragists adopted tactics from other campaigns and pioneered their own strategies to create one of the first extensive visual campaigns in American history…

Suffragists constructed popular ideals for modern American political women more than a century ago. The dominant groups’ representations of themselves as virtuous white women in their visual propaganda led many contemporaries to expect that women would cast their votes as a bloc to improve society. The suffrage message proved so effective that because no such bloc ever emerged, even scholars have argued that women’s ballots did not make much difference. To this day, the suffragists’ successful visual campaign to associate political womanhood with family values has obliged prominent women to negotiate their public images in terms of their statuses as mothers, wives, daughters, and potential mothers…

This book analyzes over a century of public political images that Americans continue to respond to, negotiate with, and challenge. From eighteenth-century woodblock engravings through twentieth-century photographic halftones, political leaders took advantage of improvements in image technology and the public’s fascination with pictures to revolutionize politics. From engraved cartoons to lithographic posters, suffragists developed strategies for each new visual medium. Widely distributed pictures offered a fast, inexpensive way to influence Americans throughout the expanding nation. This book examines popular pictures, rather than personal ones intended for family and friends, because they reveal shared ideas. These public images were at the heart of the development of a shared national visual language, composed of symbols and gendered conventions. This language helped fuel the rise of mass society and the highly visual culture of twenty-first-century life.

Images are political. We acknowledge this truth today, but they are often an overlooked register of political argument in the past. The pictures that flooded into parlors defined and reflected popular conceptions of power. Engravings and photographs do not simply illustrate a person or historical event. Artists, editors, and publishers printed them to make arguments, and public pictures conveyed those arguments to many. An image’s content, medium, and relationship to contemporaneous pictures point to a broader story. The images that suffragists and their opponents sold are just as important as the pamphlets they wrote.

Female reformers launched one of the longest and earliest coordinated visual campaigns. They combatted negative representations peddled by opponents and strategically controlled visual representations of themselves for political ends. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, women rarely had enough power or money to counter pervasive and profitable sexist imagery. During the mid-nineteenth century, individual activists led piecemeal efforts, but by the 1890s, suffragists enlisted press committees and professionals to distribute imagery across the nation. As suffragists honed their visual campaign and constructed an appealing image of political women, mainstream publications gradually began to feature their propaganda. By the 1910s, most publications featured imagery that suffragists designed, influenced, or staged (as in the case of protest photographs). Building on recent studies of race and visual politics during the antislavery and civil rights movements, this book highlights the relationship between gender and visual politics over the course of a century.

Allison K. Lange is associate professor of history at Wentworth Institute of Technology.