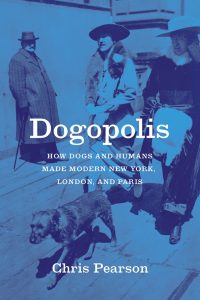

Read an Excerpt from “Dogopolis: How Dogs and Humans Made Modern New York, London, and Paris” by Chris Pearson

This October marks the fortieth anniversary of the American Humane Society’s Adopt-A-Dog Month, a holiday the many canine lovers here at UCP are more than happy to celebrate. Appropriately, we’re pleased to share an excerpt from Chris Pearson’s new book, Dogopolis: How Dogs and Humans Made Modern New York, London, and Paris, which “traces the development of the profoundly entangled relationship between humans and dogs in modern cities” and details how our pets became an inextricable part of the modern urban populace.

Emerging during the Middle Ages, the word pet came from the French word for “little” (petit) and referred to the small dog breeds often owned by women. Pet keeping was informed by broader emotional histories: in eighteenth-century Britain, the elevation of sympathy to the height of human emotional refinement provided fertile conditions for pet keeping there. Unlike ownerless strays, pet dogs lived in households and were intended to be petted. Pet keeping grew in popularity over the course of the nineteenth century. This was due in part to rising living standards and the seamless insertion of pets into the middle-class domestic ethos that venerated private and comfortable houses and apartments, and found a spatial form in new architectural styles, such as the Haussmann-era Parisian apartment. Pet dogs were said to improve the emotional sensitivity of the humans who cared for them, and as emotional creatures they deserved kindness from their human family. Loving narratives and feelings clung to pet dogs within the enclosed space of the home. Books, paintings, photographs, and newspaper articles celebrated these canines as loyal household members who comforted humans and protected the home from intruders. According to the editor of British hunting publication the Field, John Henry Walsh (known as Stonehenge), Saint Bernards made excellent guard dogs due to their “instinctive dislike to tramps and vagabonds.”

Strays—as dogs outside the home—troubled the middle-class veneration of domesticity and its associated feelings of security, love, cleanliness, and comfort. They exposed the limits of these emotional standards, as their very existence showed that dogs could survive, even thrive, outside the bourgeois interior world. As pets slotted into the middle-class ideas of domesticity and affection, strays without a human home were treated as openly aggressive to the idealized and loving family. Without human contact, strays were said to become “quarrelsome” and “aggressive.” They set themselves on pet dogs, who, having become more “docile” in human company, fared poorly in street brawls with them. Furthermore, some observers worried that allowing pet dogs to roam would undermine domestic stability and the balance between affection and domination within pet-keeping households. Warned one French authority, “flânerie” (strolling) would give pet dogs a “taste for independence,” making them less submissive. A wayward pet dog exposed the fiction of the private and frictionless middle-class home cut off from the public world. Straying undermined order inside and outside the home.

Pet dogs also received some bad press. Critical commentators argued that the pampered, selfish, and spoiled pets of the upper and middle classes consumed too much food, spread diseases, and bit innocent bystanders. British physicians asserted in 1878 that “the pleasure dogs kept by the richer classes are scarcely less a source of danger and extravagance [than those of the poor], for they appear very predisposed to rabies.” Dog loathers mocked what they saw as owners’ excessive love for their pets. Critics singled out bourgeois women who fawned over their lap and toy dogs, overfeeding and under exercising them. And the supposedly spoiled and pampered pet dogs of wealthy women who dined in fancy restaurants like Sherry’s in Manhattan were easy targets for male journalists and commentators. These men attacked what they saw as disproportionate female sentimentality that led women to treat dogs like dolls or children. More damningly, their overbearing love for their pets resulted in an inability to train their dogs effectively. Some female dog lovers also expressed concern. One was so aghast at how overly sentimental female owners spoiled their dogs that she published a book that aimed to correct their ways. These critiques of mawkish and emotionally deficient female pet owners shed light on the unequal gendered dynamics and divisions within the cult of domesticity. Middle-class women were charged with loving and caring for pets (and other members of the household) but were taken to task when their love and care seemed excessive, inappropriate, or harmful. The judgments heaped on them also exposed the fragility of the domestic private sphere by serving up their pet-keeping practices as objects of public deliberation and intrusion. Men may also have been unsettled by female dog owners’ close bond with dogs, animals bound up in Victorian notions of masculinity. Female pet keeping undermined the popular portrayals of hunting, sporting, and pet dogs as companions for men, with dogs and their male owners sharing the emotional qualities of chivalry, loyalty, bravery, steadfastness, and heroism.

Pet keeping lent itself to mockery. But the pet dog nonetheless became the acceptable furry face of human-canine relations in the modern city as well as the deserved object of human attention, love, and compassion.

Chris Pearson is a senior lecturer in twentieth-century history at the University of Liverpool.

Dogopolis is available now from our website or your favorite bookseller.