Three Questions with Robert Cozzolino, Editor of “Supernatural America”

America is haunted, marked by a violent history that is an inescapable and unsettled part of the nation’s heritage. A new exhibition and catalog, Supernatural America, brings together two hundred years of this haunted history, showcasing the paranormal in American Art. We spoke with the show’s curator, Robert Cozzolino, to hear a little more about the inspiration for this project and about some of the works that are included.

Could you say a bit about what got you started with the idea for this exhibition?

The exhibition has its origins in many converging threads in my life. I was born on Halloween, following in the footsteps of my maternal grandfather, Thomas McCann, who also had that birthday. I have been fascinated with all things having to do with the supernatural/paranormal since I was a child. I have experienced otherworldly phenomena and have met dozens of people who also have had experiences of ghosts, spirit contact, poltergeists, and other things we might say are supernatural. I grew up in Chicago and went to UIC as an undergrad. Some art history professors had encouraged me to take an internship at the Art Institute and while there I worked on artist Ivan Albright’s (1897-1983) notebooks. I had been amazed by his work when I first encountered it as a senior in high school and while I was at the Art Institute I heard that the late Courtney Donnell was organizing a retrospective; I volunteered for her and eventually worked on the exhibition and catalog with her. While spending hours looking at his paintings close up I also read his writings that span six decades. I came away believing that his unusual painting technique was not about death and decay, but an attempt to paint matter and spirit simultaneously; he was consumed with the idea that he might make the intangible tangible through his painting method and make the unseen lifeforce animate the paintings. That interest came from his immersion in Spiritualism, Theosophy, and other religious and philosophical ideas about the soul and spirit world. He wrote about ghost experiences, and family members told me that “the paranormal was considered normal in the Albright family.” Even late in life, he wrote about UFOs being connected to spiritual beings. I wondered, “how many other artists were invested in these interests?” That started me keeping an eye out for signs of this stuff across periods and materials in American art.

What is the significance of the supernatural in American art today?

I have found that supernatural interests are a consistent throughline in American culture. It is everywhere and in unlikely places. I think that an awareness of the spectral has been an underlying state of consciousness in American culture. It pops up in innumerable forms of entertainment—like film, novels, comics, graphic novels, podcasts, TV shows—but it is also a critical part of the country’s identity for painful reasons. So many cultural traditions see communities honoring ancestors and loved ones who passed, and in the time of the pandemic, that has been an urgent enduring need. The United States also still has yet to fully come to terms with the violent acts that brought it into being—genocide of Indigenous people, slavery, and the ongoing racial violence that affects every part of our society. If we were not thinking about how these things manifest in daily life before 2020, the uprisings in the wake of more murders of Black people made it clear that the ghosts of the past are emphatically present, demand to be dealt with and will not rest until they have been seen and honored. Many contemporary artists make art about this aspect of haunting, and they are critical contributors to the exhibition and book, including John Jota Leanos.

Do you have a few favorite pieces that you’d like to highlight?

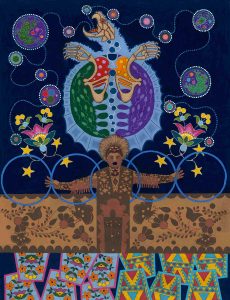

I was honored to be able to include the work of several artists who were practicing mediums in the Spiritualist church. Artists such as Agatha Wojciechowsky who disavowed responsibility for their art, but asserted that it was the work of spirits that entered their bodies to make the work or write messages. I have included art from history (18th-early 20th century) and today, to serve the theme of the past and present speaking to one another. Renee Stout is one of those contemporary artists who have a major piece in the exhibition and also wrote about it in the book. Her piece The Rootworker’s Worktable is a tour-de-force of her practice as a maker—sculptor, painter—incorporating found items, glass she made during a residency, etc. It imagines a healer’s space, with bottles containing the elements that would go into potions, tinctures, cures, etc for all sorts of physical and spiritual ailments. Finally—a Minnesota-based artist named Chholing Taha is also one of my favorites in the project; she is represented by two paintings made after a complete and detailed vision was revealed to her by spirits based on experiences she had alone and in community. The critical thing about the show is that most (though not all) of the artists included had these experiences—they had first-hand encounters. And taking that seriously—and treating it with respect has been the aim all along. Collaborating with artists about that part of their lives has been extremely meaningful.

The Supernatural America exhibition started at the Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo, OH) from June-September 2021, is currently on view at the Speed Art Museum (Louisville, KY) from October 2021-January 2022, and will move to the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Minneapolis, MN) from February-May 2022.

Supernatural America is available now from our website or your favorite bookseller.