Read an Excerpt from our #ReadUCP Book Club Pick “The Contested Crown: Repatriation Politics between Europe and Mexico”

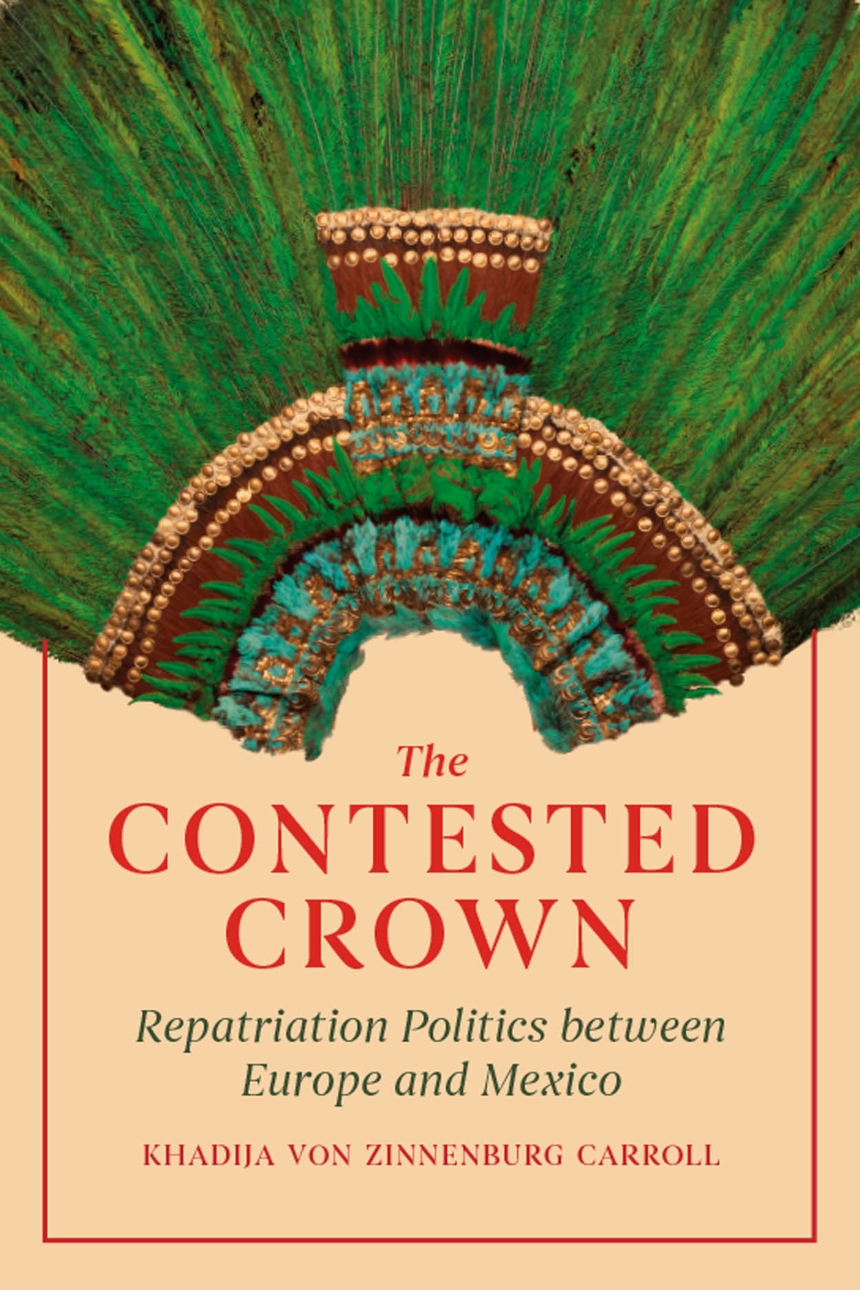

Our #ReadUCP Twitter Book Club is back! This March we are reading The Contested Crown: Repatriation Politics between Europe and Mexico by Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll. In The Contested Crown, von Zinnenburg Carroll meditates on the case of a spectacular feather headdress believed to have belonged to Montezuma, the last emperor of the Aztecs. Both the biography of a cultural object and a history of collecting and colonizing, this book offers an artist’s perspective on the creative potentials of repatriation. Carroll compares Holocaust and colonial ethical claims, and she considers relationships between indigenous people, international law and the museums that amass global treasures, the significance of copies, and how conservation science shapes collections. Illustrated with diagrams and rare archival material, this book brings together global history, European history, and material culture around this fascinating object and the debates about repatriation.

Below is a brief excerpt from the introduction to the book, and since we’ll know you’ll want to read more, you can use the code READUCP to buy the book from our website for 30% off. Then, mark your calendars to join our Twitter Book Club Meet-up with the author for a Q & A on March 31 at 2:00 PM CT. Just follow the hashtag #ReadUCP.

In a crypt below the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, now housing some of the city’s principal museums, is found the storage area for less sensitive materials from their collections. Among them, several Aztec stone sculptures are assembled on temporary metal racks. Curled up on a shelf is the feathered serpent deity Quetzalcóatl, the geometry of its scales and plumage deeply incised in stone. The stone effigies are unaffected by the damp in the underground passageways, and the catacombs are seldom visited.

In Mexico, subterranean civic structures are romanticized as part of a more ancient world, submerged beneath the modern. In Aztec philosophy, this is the realm of Mictlāntēcuhtli, lord of the deepest region of the underworld, the last level in which the dead remain. In Vienna, such spaces have different associations. The basement below the Palace was once part of a central underground corridor, connecting a city once used by the Nazis. A few floors above, the sound of classical stringed instruments reverberates from the walls; but below ground, these hidden passageways have witnessed many murders. The ring of boots on cobbles lingers. It is always dark in this subterranean stratum of Vienna. Some nights are gloomier than others; but not even the blackest night can provide as effective a cover as an underground passage, as the Viennese have long known. In times gone by they built passages large enough to accommodate a carriage drawn by two horses, to carry the royal family from the center of the city to a place of safety in times of crisis. Over the centuries, the high-ranking in society have been able to escape the wrath of the masses using these same routes. Opposite the museum is another node in the underground network, situated beneath the parliament building that is crowned by sculpted chariots drawing eight winged Nikes. When they were undergoing restoration the sculptures were X-rayed, revealing that the horses’ bellies were full of the corpses of dead birds. Doves had nested in the cavity of the sculpted horses’ bowels, and the acid produced by the excrement of the dead was corroding the sculptures from the inside. Conservators removed the remains of the doves amid the stench of rot, and the monumental horses and winged figures that mark the site of the Viennese parliament were restored.

Facing these sculpted figures is the balcony of the Hof-burg Palace, from which Hitler made his annexation speech to a crowded Heldenplatz (Heroes’ Square) on March 15, 1938. It is on this site that my story begins, although it will go back and forth in both time and space between the Aztec Empire (now Mexico) and Europe, its chronology spanning five hundred years of history embodied in the five hundred feathers that make up one headdress, (also referred to as a crown since the twentieth century). The headdress is held in the Hofburg Palace, and this unique, ancient Aztec artifact symbolizes the repatriation debates that unfold in this book. A prize of the Spanish conquest over the Aztec Empire in the sixteenth century, El Penacho is a treasure that troubles the ethnographic museum of Vienna.1 Too valuable and, some argue, too fragile to return, it has become so notorious through protests demanding its repatriation that it now overshadows Mexican-Austrian relations.

Today the feather headdress is displayed in the Welt- museum; previously called the Museum für Völkerkunde, which has occupied part of the Hofburg Palace since 1928. In the museum’s kaleidoscope of grand, colored marble rooms, the gallery in which the headdress was most recently displayed is a dark labyrinth, with the vitrine containing the feather headdress at its center. Often when I linger here a visitor will ask me, “How did the last remaining Aztec feather crown come to be in Vienna?”

The Hofburg Palace was the seat of the Habsburgs in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Austria’s brief reign over Mexico in the 1860s, little known internationally, is an episode in nineteenth-century colonial history that highlights the fragility of any crown. When the Habsburg crown fell in Mexico, it became conflated with the feather crown that symbolizes the Aztec monarch, Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (Motecuhzoma the Younger, 1466–1520). A ceremonial headdress rather than a crown, it was taken after Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin was murdered during the invasion by Hernán Cortés, the infamous conquistador who led the Spanish forces to conquer the capital of the Aztecs, present-day Mexico City.

In the sixteenth century, the Habsburg Empire spanned Europe, from Austria to the Netherlands and Spain, Bohemia, parts of Hungary, Croatia, Silesia. Through this network, formed by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, artifacts from the New World entered Europe through ports such as Antwerp. Although the Habsburg Empire included Madrid, these artifacts came directly to Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, the home of Charles’s nephew, Ferdinand II, an avid art collector. In popular imagination, Ferdinand’s cousin, Maximilian, the Habsburg emperor of the short-lived second Mexican Empire from 1864 to 1867, sent the headdress to Vienna. In fact, Maximilian did not arrive in Mexico until some three hundred years after the feather headdress had departed. This mistaken provenance speaks volumes about the lingering presence of colonialism within the relationship between Mexico and Austria.

The assumed connection between the history of the headdress and Maximilian is but one of a surreal but impassioned set of associations that today tie Mexicans and Austrians together.

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll is an Austrian-Australian artist and historian. She is chair of Global Art at the University of Birmingham and professor at the Central European University. She is the author of Art in the Time of Colony, The Importance of Being Anachronistic, Botanical Drift, and Bordered Lives.