“The Boundaries of Knowable Nature”: The Chinese Exiles of “Knowing Manchuria”

At the intersection of China, Russia, Korea, and Mongolia, Manchuria is known as a site of war and environmental extremes, where projects of political control intersected with projects designed to make sense of Manchuria’s multiple environments. Covering more than 500,000 square miles, Manchuria’s landscapes include temperate rainforests, deserts, prairies, cultivated plains, wetlands, and Siberian taiga. With analysis spanning the seventeenth century to the present day, Knowing Manchuria by Ruth Rogaski reveals how an array of historical actors—Manchu shamans, Russian botanists, Korean mathematicians, Japanese bacteriologists, American paleontologists, and indigenous hunters—made sense of the Manchurian frontier through embodied engagement with specific environments. The Los Angeles Review of Books called Knowing Manchuria “a crucial contribution to the understandings of East Asia, of imperialism and indigeneity, and of science and the modern state.”

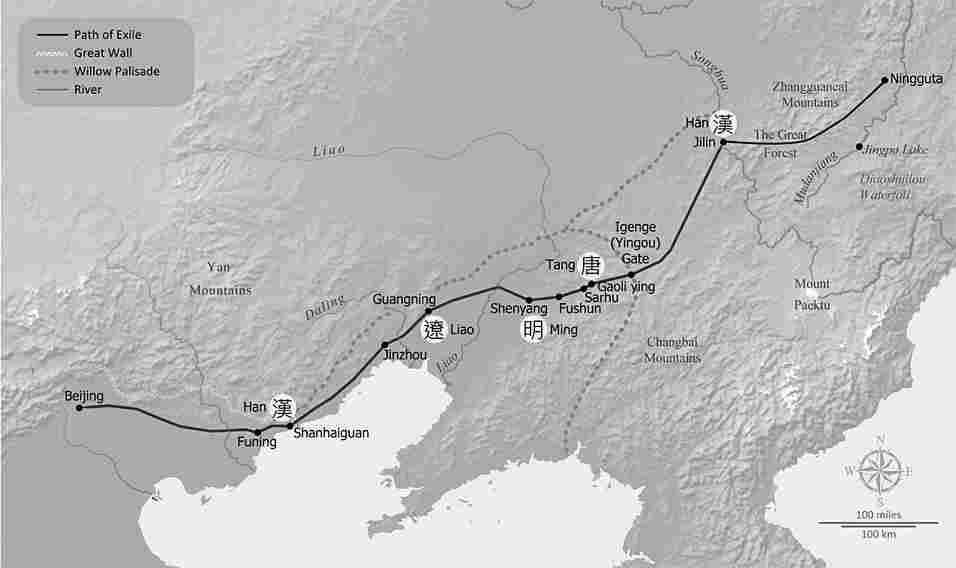

The book’s first chapter, “Landscapes of Exile,” focuses on Wu Zhaoqian, a Chinese poet banished to Manchuria in 1659. His exile began shortly after a violent transition from the Ming dynasty, a Han-led government, to the Qing, led by the Manchus. Rogaski traces Wu’s four-month journey from Beijing to Ningguta, a military outpost at the northern limits of the empire, noting the geographical features he encountered as well as the social, cultural, and political experiences that informed his observations. “By walking northeast with the exiles,” Rogaski writes, “we see Manchuria unfold as a process of discovery: the meeting of human perception with the physical presence of an alien territory.”

Below are seven memorable observations from “Landscapes of Exile.”

Wu was exiled for failing an exam. Born in 1631 to an illustrious Han family in the city of Wujiang, Wu grew up in the Yangtze River delta, a region concentrated with wealth, libraries, and literati society. A literary celebrity renowned for his ability to describe the natural environment, he excelled at the fu genre, a form of poetry that categorized and described China’s plants, animals, mountains, rivers, and forests. Given his literary talents, Wu might have ascended to a position of power as a scholar-official if his imperial examination results had not been vacated, the fallout of a bribery scandal. He and dozens of other young men were summoned to Beijing to take the exams again, while Manchu guards holding scimitars kept watch. Wu didn’t write a word. “Scholars have offered little insight into why Wu failed to demonstrate brilliance under these conditions,” Rogaski notes. “Was it an intentional act of political resistance against the alien Qing, or simply the result of paralyzing fear?” For his defiance, he was banished to Ningguta, where he remained for twenty-four years.

Chinese exiles made important contributions to the global age of discovery. The poets and scholars who traveled from China proper to Manchuria—and elsewhere in Asia—were, like the explorers from early-modern Europe, literate voyagers who interpreted distant surroundings for audiences back home. “For almost two millennia, scholars who ran afoul of emperors had been banished to the frontier regions of China’s ever-shifting imperial expanse,” Rogaski writes. “Whether they were sent to the foothills of the Himalayas or the tropics of Vietnam, such men had anchored Chinese understandings of nature at remote sites across multiple dynasties.” The seventeenth-century exiles tried to survey new ecosystems, landscapes, flora, and fauna by relying on received wisdom grounded in ancient texts. They also favored “an aesthetic of nostalgia,” looking for evidence of human history within the non-human environment: detritus from battles, ruined villages, and other specters of bygone eras.

Wu’s poems initially evoked literati cliches about the northern landscape. Associating the northern regions with war and dislocation, Han writers like Li Bo, Du Fu, Bai Juyi, and others described Manchuria as a landscape rife with destruction. “These frontier poems are full of exhausted soldiers, conscripted laborers, and exiled officials who are reluctant observers of a foreboding environment,” Rogaski explains. “Through their tearful eyes, they see bones of dead soldiers piled in white heaps, sterile brown-and-gray vistas or landscapes covered in snow and ice, with the ruins of fallen cities standing mute in the distance.” Wu’s work also employs these tropes, especially as he describes the beginning of his journey north. But later, Rogaski writes that “Wu entered a forested world where frontier-poetry allusions no longer held.” During the final leg of his journey, he passed through the Zhangguancai Mountains, an area of rainy, old growth forest, a landscape utterly unlike the threadbare imagery Han poets used to describe the north. The forest fascinated Wu. He describes the area in his poem “The Great Wuji,” sketching “a flood of trees rings the sky for more than a hundred miles— / Dense pines that have covered the land for more than a thousand years.”

The Chinese exiles were frustrated that their new locale seemed to be devoid of written history. In Ningguta, Wu joined a community of learned exiles who struggled to reconcile their knowledge of natural history with their new environment. Dynastic histories and ancient geographies did not mention Ningguta, and Han scholars had not ventured there to record its plant and animal life. One exile, Zhang Jinyan, believed the exiles “were in essence responsible for creating valid knowledge about the environment,” Rogaski writes. Disregarding the contributions of local people, who he was convinced were uninformed about the mountains and forests, Zhang concluded that Han exiles, attuned to the novelty of their environment and classically educated, were ideally suited to name, categorize, and record the landscape. Exiles should look beyond their feelings about exile or Ningguta, he maintained, to observe the natural world directly without emotional influence. Rather than lean on ancient texts, Zhang argued that Chinese scholars should explore and use their own senses and knowledge to study far-flung regions. While exiled, Zhang wrote Record of Ningguta’s Mountains and Waters, a detailed account of regional geography based on first-person observation.

The exiles enjoyed trips into the countryside that were part leisure, part geographical exploration. Trips to nearby mountains and rivers occupied the exiles, excursions that echoed the leisure activities of the Han elite, but also served as opportunities to learn about the environment. Wu narrates a whitewater-rafting expedition in one poem, evoking the ducks, geese, “fishlike dragons,” an “azure spring,” and the excitement of the cascade: “Suddenly we hear the shallow rapids thunder; then in a blink of an eye, the waves settle again into silence. / An unknown wind drives the skiffs, we are stunned at how fast the snowy peaks go by. . . .”

The exiles weren’t sure how to apply natural knowledge from China proper to Manchuria. Did the principles they’d learned south of the Great Wall hold in this distant region? Fascinated by mountains, Zhang set out to rank Manchurian ranges in ways consistent with Chinese intellectual traditions. Mountains were ordered not only by height but within a hierarchy of the five cardinal directions. China’s most famous peaks were sacred mountains in each of these directions, all located within China proper. Zhang noted that ranges of Shanxi faced the region’s sacred mountain, Hengshuan; this was because the mountains, a representation of the earth’s qi, emanated from a spiritual point of origin. The mountains of Ningguta, he claimed, faced another majestic peak, Changbaishan, in the same way. “Through analogy, he postulated that the mountains of the Ningguta region were arrayed in a way that followed the patterns of nature evinced in China below the Great Wall,” Rogaski writes, adding that, “with this meditation on mountains, Zhang put forth a basic claim: this place might be beyond the borders of civilization, but it was entirely within the boundaries of knowable nature.”

The exiles’ attempts at writing dispassionate observations about the environment in Manchuria are an important chapter in the history of objectivity. Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have argued that objectivity, as it emerged in Europe, entailed “a belief in a bedrock reality independent of human observers” and a “desire for emotional detachment.” Chinese exiles in seventeenth-century Manchuria similarly tried to put aside their emotions and engage directly with their environment. If objectivity is “first and foremost. . . . the suppression of some aspect of the self,” then the natural knowledge of the Ningguta exiles, even if it was expressed in poetry, should be included in the history of this concept.

Ruth Rogaski is associate professor of history and Asian studies at Vanderbilt University. She is the author of Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China.

Knowing Manchuria is available now from our website or your favorite bookseller.