Five Questions with Jeffrey Saletnik, author of “Josef Albers, Late Modernism, and Pedagogic Form”

The great artist and teacher Josef Albers helped shape the Bauhaus school in Germany, established art and design programs and Yale University and the Black Mountain College in North Carolina, and created books about color theory that have informed generations. With his new book, Josef Albers, Late Modernism, and Pedagogic Form, Jeffrey Saletnik explores the pedagogy of Albers, analyzing his teaching methods and his influence on other artists. In this post, we chat with Jeffrey to get some insight into the book and Albers.

What initially drew you to Josef Albers?

I came to Josef Albers through an interest in the afterlife of the Bauhaus, the German design school where Albers had been a student and later a teacher before he emigrated to the United States in 1933. In the United States, he taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where his students included Ruth Asawa, Susan Weil, Ray Johnson, and Robert Rauschenberg, and later (from 1950) at Yale University, where Sheila Hicks, Neil Welliver, and Richard Anuszkiewicz are counted among his students. It seemed to me that one of the ways in which the Bauhaus extended beyond its brief fourteen-year existence in Germany was through the elaboration of educational principles practiced at the school in diaspora. I wanted to understand Albers’s role toward that end.

Albers’s curriculum in design, drawing, and color was inclusive and pragmatic, which might help to explain its applicability. It was a gateway for all students regardless of their prior experience.

Albers’s practices are still widely employed in art classrooms today—why do you think that is?

I am not an artist, let alone a teaching artist, and thus I can’t speak from a position of first-hand experience, but Albers’s curriculum in design, drawing, and color was inclusive and pragmatic, which might help to explain its applicability. It was a gateway for all students regardless of their prior experience. Indeed, this was especially the case as it was practiced in the context of a liberal arts curriculum at Black Mountain, where many of the students who took Albers’s classes had no intention of pursuing careers as artists. There were comparatively few barriers to access—including with respect to student investment in supplies, etc. This may have been a consequence of the curriculum initially having been developed in a period of shortages in post-WWI Germany and later at a fledgling college during the Second World War. Whatever was at hand could be put to use: kitchen scraps and poured concrete became materials for investigation in the design curriculum; students made drawings on raw newsprint rather than fine paper; magazine clippings initially were used in the color instruction. But these were more than mere practical solutions due to economic conditions, they also were pedagogical decisions—students were encouraged to view all matter as potential material for art making.

What are some ways that Albers’s pedagogical training in Germany shows up in his own artwork and teaching?

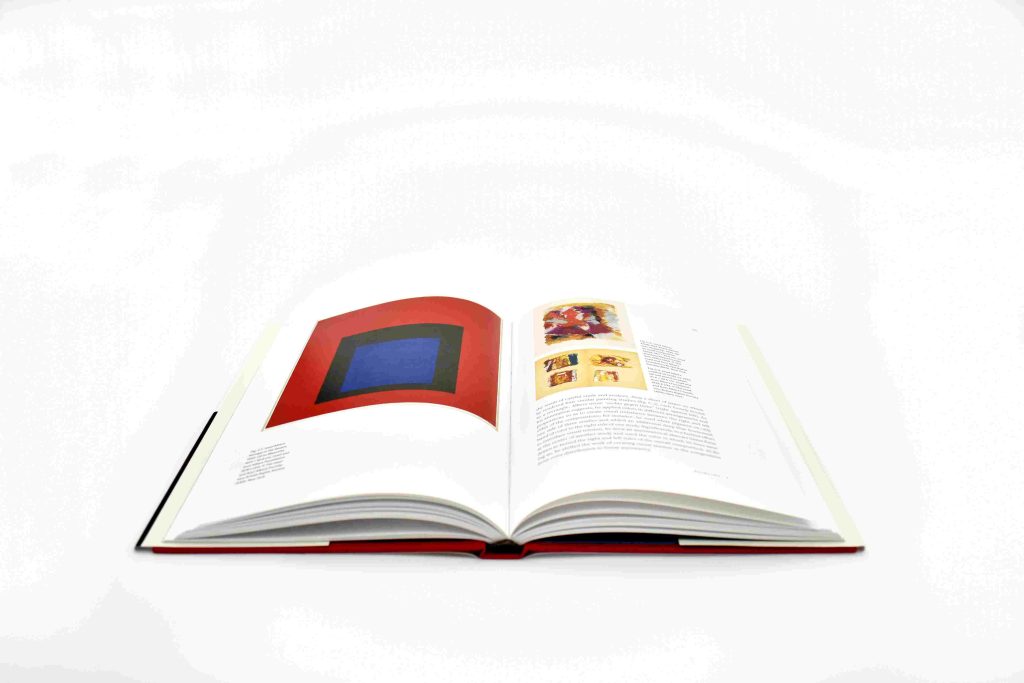

Albers, who had been a primary school teacher for several years before he enrolled at the Bauhaus, brought a thorough understanding of the history and theory of education to bear upon his teaching at the Bauhaus, Black Mountain, and Yale. The notion of the Arbeitsschule or activity school informed his “hands-on” instructional methodology, as research in child and applied psychology known to him through his teacher training did his color instruction. In my view, there are aspects of Albers’s art practice that relate to his pedagogy as well. Albers’s Homage to the Square series of paintings and prints, for instance, could be seen as demonstration pieces through which viewers experience various kinds of color interaction in isolation, in the museum or gallery; in so doing, perhaps they are made aware of the dynamics of color interaction more generally and see differently when they look away.

Are there artists working today whose practices show evidence of Albers’s pedagogy?

This is a difficult question because how an artist interprets the educational practices they experience as a student varies tremendously. But, as I contend in the book, it is important for us to consider relationships between pedagogy and practice—to consider to what extent the frameworks in which one comes to understand the work of being an artist helps to structure how one works and perhaps the work one makes. This is difficult to discern. And with respect to Albers’s pedagogy, there is the further complication that many artists who may not have been educated according to a curriculum in some way indebted to Albers may nevertheless know his text Interaction of Color, which has been in print in various forms since 1963. In this case, further mediation is involved—there is further remove from the activity of Albers’s curriculum as it is presented in the text. Yet presumably the core message that color perception is conditional and in constant flux is received.

But, to answer your question: in the book, I elaborate on how the artistic practices of Eva Hesse and Richard Serra correspond to aspects of Albers’s pedagogy, which both of these artists knew; however, artists with little or no connection to Albers’s pedagogy and, for example, who employ perception as material in their practices also could be seen as being in dialogue with aspects of Albers’s instruction—Robert Irwin and Olafur Eliasson come to mind. Eliasson also is committed to innovative teaching, as evinced by the activities of his (now closed) Institut für Raumexperimente, where the activity of education itself often also was a creative act.

Do you foresee Albers’s influence continuing on—or shifting—as modernism moves further into the past?

Only time will tell! But I suspect that Albers will be part of conversations on teaching art for some time to come.

Jeffrey Saletnik is associate professor of art history at Indiana University Bloomington. He is coeditor of Bauhaus Construct: Fashioning Identity, Discourse, and Modernism.

Josef Albers, Late Modernism, and Pedagogic Form is available now from our website or your favorite bookseller.