Why is the Bhimrao Ambedkar and John Dewey Story so Important to Tell? | A Guest Post from Scott R. Stroud

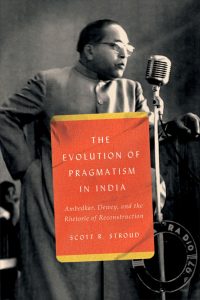

In The Evolution of Pragmatism in India: Ambedkar, Dewey, and the Rhetoric of Reconstruction, Scott R. Stroud relates the untold story of how the Indian reformer Bhimrao Ambedkar embraced and reimagined John Dewey’s pragmatism throughout his work. In the guest post below, Stroud offers both an introduction to Ambedkar for the uninitiated and a brief sketch of why this story is important to the history of philosophy, democracy, and rhetoric.

When Bhimrao Ambedkar, a prominent political leader and activist in twentieth-century India, reached New York in June 1952, he learned that his teacher, John Dewey, had passed away. Ambedkar was being called back to Columbia University—the place of his early education from 1913 to 1916—to receive an honorary doctorate in recognition of his role in the drafting of independent India’s democratic constitution. Ambedkar wrote to his wife Savita to express the depth of his sadness: “I am so sorry. I owe all my intellectual life to him. He was a wonderful man.” Many have mentioned this line from Ambedkar, but no one has much more to say on the story of Ambedkar’s relationship with the thought of John Dewey. I hope to change this lack with my recent book, The Evolution of Pragmatism in India.

Ambedkar is an important figure in Indian politics and history, given his role in creating India as the world’s largest democracy and his tireless struggles on behalf of his fellow “untouchables” in the battle against caste oppression. Many in India know of parts of Ambedkar’s impressive and complex story, but few in the West have even a passing familiarity with him, his accomplishments, and his voluminous scholarly writings. Why does Ambedkar—and his relationship to Dewey’s thought—matter, especially for those like me in the West? Let me sketch out four reasons why the story of Dewey and Ambedkar—and the evolution of pragmatism in India—matter.

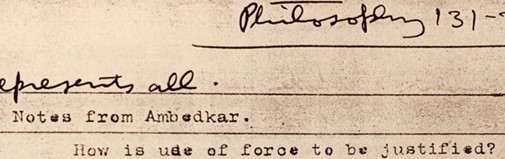

First, Ambedkar’s relationship with Dewey—and Dewey’s thought—spanned his lifetime and mattered significantly for the development of this important Indian leader. Ambedkar was active in the politics of both pre- and post-independence India; much of his thinking and activism were driven by concerns of democracy and political equality that were in direct conversation with Dewey’s philosophy. Using previously unnoticed lecture notes by Ambedkar, his classmates, and Dewey himself, this book takes us into the classrooms Ambedkar shared with Dewey at Columbia University 1913-1916. We see what he heard and read from Dewey, which allows us to also notice what he extends, changes, or rejects from Dewey at important points in his own thought.

Second, Ambedkar’s story represents a new chapter in the evolution of pragmatist thought around the globe. Dewey influenced thinkers in China, Japan, Europe, and elsewhere, but no one has told the story of his thought and its relation to India. Ambedkar and his creative engagement with Dewey’s philosophy can be seen as extending and evolving the pragmatist tradition in South Asia. There is no common doctrine among those we call pragmatists, but we can capture the sense of Ambedkar’s respect for Dewey and the use of some of Dewey’s emphases (such as democracy as a habit and respect for human personality) by talking about him as an Indian pragmatist. Like Hu Shih (Ambedkar’s classmate in Dewey’s 1915-1916 course) in China, Ambedkar does not repeat what Dewey writes or says. But he takes inspiration from certain ideas, ideals, and methods that Dewey practiced or theorized about, and we can learn much about pragmatism’s possibilities by learning about Ambedkar’s creative and novel philosophy.

Third, Ambedkar’s engagement with Dewey’s thought tells us new things about the powers of rhetoric and persuasion. Unlike his teacher, Dewey, he was a powerful and commanding orator. Ambedkar’s speeches would command audiences in the thousands and motivate his fellow Dalits (the self-chosen word for “untouchable”) to demand respect from others. In the 1950s, Ambedkar led a powerful movement among the Dalits to convert to Buddhism—and out of the strictures of the caste system. The Evolution of Pragmatism dives into Ambedkar’s strategies of persuasion and finds that they represent an evolution of pragmatism’s reconstructive method. Our words don’t just mirror the world—they can be used to change it.

Fourth, examining the Dewey-Ambedkar relationship can shed more light on the topics of democracy, caste, and social justice. Ambedkar, like Dewey, believed that democracy went beyond and below political institutions and formal decision-making procedures. It represented a way of life or certain habits of how individuals see and value their fellow citizens. Ambedkar’s story is important for those of us in the West because of two innovations. He gives us a new entry to our theories of democracy. As I explore in the book, Ambedkar finds the sort of semi-transcendent ideals mentioned by Dewey to be central to his efforts. Liberty, equality, and fraternity are mentioned in the class he took with Dewey, but Dewey leaves them behind; Ambedkar would make them central to his critique of Hinduism and the caste system. They were not timeless, as the sacred texts that underwrote caste claimed, nor were they emergent from his native tradition that placed the restrictions of caste on his shoulders. They could be used to point out what is wrong in any given society since they point to interconnected aspects of community experience. The challenge for democracy is to find a way to balance freedom, equal treatment, and fellow-feeling among individuals who often disagree vehemently.

Ambedkar also gives us a new way to think through our struggles with social justice. In many cases, our stories about social justice have been confined to narratives of resisting colonialism, racism, and sexism. Ambedkar can serve a valuable role in showing us how anti-caste philosophy fits into an expanded notion of social justice. His main problematic was showing how caste divisions were cracks in the solid community we sought with our ideals of democracy. Like Dewey, he desired a community animated by shared interests and freedom. Caste is among those practices that essentialize and divide individuals. Dewey did not know much about caste, but as I show in my book, Ambedkar’s appropriation of certain parts of Dewey’s pragmatism served his need of resisting caste as undemocratic. Ambedkar becomes both a powerful pragmatist theorist of democracy and an anti-caste intellectual we can add to our courses in the West.

Scott R. Stroud is associate professor of communication studies and program director for media ethics at the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of John Dewey and the Artful Life and Kant and the Promise of Rhetoric, as well as the co-founder of India’s first Center for Dewey Studies at Savitribai Phule Pune University.

The Evolution of Pragmatism in India is available now from our website and your favorite bookseller.