Five Questions with Jill Pruetz, author of “Apes on the Edge”

Fongoli chimpanzees are unique for many reasons. Their female hunters are the only apes that regularly hunt with tools, seeking out tiny bush babies with wooden spears. Unlike most other chimps, these apes fear neither water nor fire, using shallow pools to cool off in the Senegalese heat. Up to 90 percent of their home range burns annually—the result of human hunting or clearing for gold mining—and Fongoli chimpanzees have learned to predict the movement of such fires and to avoid them.

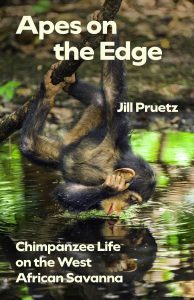

The study of Fongoli chimps is also unique. While most primate research occurs in isolated reserves, Fongoli chimpanzees live alongside humans, and as primatologist and anthropologist Jill Pruetz reports, this shared habitat creates both challenges and opportunities. The issues faced by Fongoli chimpanzees—particularly food scarcity and environmental degradation—are also issues faced by their human neighbors. This connection is one reason Pruetz, who has studied Fongoli apes for over two decades, created the nonprofit Neighbor Ape in 2008 to provide for the welfare of the humans who share their landscape with apes. It is also why Pruetz decided to write Apes on the Edge: Chimpanzee Life on the West African Savanna, the first to offer readers a view of these chimps’ lives and to explain the specific conservation efforts needed to help them. Incorporating stories from Pruetz’s time in the field, including the compelling rescue of a young chimp from poachers, Apes on the Edge opens a fascinating window into primate research, conservation, and the inner workings of a very special population of our closest nonhuman relatives.

Read on for a Q&A with Pruetz about her fascinating and important work.

How did you wind up in your field, and what do you love about it?

I actually found Anthropology by taking a course during my undergraduate years at what was then Southwest Texas State University (now Texas State University, where I teach!). I kept taking courses in Anthropology and found I also loved being in the field. I ended up combining that with my love for animals, and I have been studying primates in the wild ever since. It really is extraordinary that I am able to do what I love and am passionate about as a job and career. I also love Anthropology because of how broad a discipline it is, which introduces us to such varied work. I especially like the view that we take as anthropologists, in which we should always consider the perspective of others in our research—whether they are other cultures of people or other species, like chimpanzees.

In Apes on the Edge, you write about two unique populations of primates—the chimpanzees and humans of Fongoli, Senegal—and how they interact. Can you tell us a bit about that?

I began research at Fongoli in large part because of the fact that humans and chimpanzees live alongside one another in the Fongoli area and have been for millennia, probably. After calculating chimpanzee densities in the nearby Niokolo Koba National Park as well as in the Fongoli area, I was surprised to see that they were similar. Common thinking at the time was that people were detrimental to chimpanzee populations, which is indeed the case in many parts of Africa. In Senegal, however, there are cultural taboos against harming chimpanzees, and this has conserved this species when other large mammals have disappeared. Despite this relationship, the gold rush over the past decades threatens to exterminate most chimpanzees in Senegal, which live outside of national parks. That’s what I talk about in the last chapter of my book, in particular.

While you were working on this project, what did you learn that surprised you the most?

I think I was most surprised at how difficult it was to write what I consider to be a really enjoyable book to write! Of course, I never thought writing was easy. It was wonderful to remind myself of all the anecdotes I had recorded along with my data. Some of them I would not have remembered without my trusty field notebooks, so I will never be sorry for writing down anything and everything that occurs to me while I’m with the chimpanzees. Head Fongoli researcher, Michel Sadiakho, often writes down his thoughts and feelings in his data book, and it is a joy for me to read as I sit in my office in Texas. Perhaps I could help him put his stories together for a book someday too.

I especially like the view that we take as anthropologists, in which we should always consider the perspective of others in our research—whether they are other cultures of people or other species, like chimpanzees.

Where will your research and writing take you next?

Given the continued pressures on chimpanzees and the natural landscape in southeastern Senegal, our focus at Fongoli is on conservation. That doesn’t mean that we aren’t still conducting purely scientific research. I’m collaborating with Dr. Cat Hobaiter and colleagues on the study of gestural communication at Fongoli, which hasn’t been studied much to date. One of my archaeology colleagues at Texas State University, Dr. Britt Bousman, is collaborating with me on a study of the landscape of chimpanzee tool use at Fongoli. But the Fongoli Savanna Chimpanzee Project team is focused on conserving the chimps and their landscape right now. We work with local communities as well as a corporate mining company that is working to offset the environmental effects they have incurred in their mining operations not too far from Fongoli. My Senegalese colleagues, Dr. Papa Ibnou Ndiaye and Fongoli Savanna Chimpanzee Project Codirector Dr. Landing Badji, are instrumental in engaging all of the partners in the Fongoli area in collaborative efforts. I was recently at Fongoli—in December 2024—and we followed the Fongoli chimps as they expanded their home range into the neighboring chimpanzee community’s home range. I had always predicted that the Fongoli group would ultimately push into the Bantan chimps’ range as the town of Kedougou expanded from the east, but I didn’t anticipate seeing it happen so soon. I can envision the next chapter in the Fongoli chimpanzees’ story telling the tale of how these chimpanzees—and those at Bantan—adjust to increasing human pressures. Hopefully, the story will have a happy ending.

What’s the best book you’ve read lately?

I’m a little late in reading Wicked by Gregory Maguire, but the newest infant chimpanzee at Fongoli is named “Elphaba,” so I thought I should get informed! One of the fundraisers I do for my nonprofit, Neighbor Ape, to support chimpanzee conservation and development projects for people living in the Fongoli area auctions off the opportunity to name a baby chimp at Fongoli. The last two infants were named by donors to our auction, and little Elphaba (we are using “Elfaba” to make the name fit in better with the Malinke language that is spoken locally at Fongoli) was born just last month to mother Eva. My next task is to watch the movie—I always enjoy reading books before I watch the movies, like many people I know!

Jill Pruetz is professor of anthropology at Texas State University. She has studied primates in Kenya, Nicaragua, Panama, Costa Rica, and Peru, and, since 2001, has been the principal investigator of the Fongoli Savanna Chimpanzee Project in Senegal. She is the author of The Socioecology of Adult Female Patas Monkeys and Vervets in Kenya as well as the children’s book You Can Be a Primatologist.

Apes on the Edge is available now from our website. Use the code UCPNEW at checkout to take 30% off when you order directly from us.