Babbling bonobos? The search for animal language

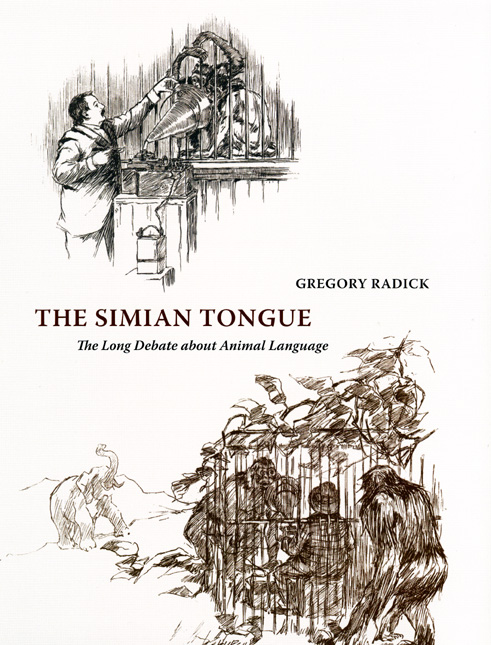

This piece on Slate Video recently caught our eye. In it, Jon Cohen visits the Great Ape Trust in Des Moines, Iowa, a research facility where inquiries into the cognitive and communication abilities of bonobos, orangutans, and apes continue on while most of the rest of the scientific community has abandoned its search for language in our closest relatives. A fascinating topic, no doubt, but check out that well-thumbed and post-it-laden book Cohen holds at minute mark 1:20—that’s our very own title, The Simian Tongue: The Long Debate about Animal Language by Gregory Radick. For those fascinated by Cohen’s report, Radick’s book offers a detailed history behind the kind of research that continues today in Iowa.

In the early 1890s an amateur scientist named Richard L. Garner used the a phonograph to record monkey calls, play them back to the monkeys, and observe their reactions. From these experiments, Garner judged that he had discovered “the simian tongue,” made up of words he was beginning to translate, which contained the rudiments out of which human language evolved. His experiments made him famous; but his reputation was damaged irreparably after a trip to Africa led to accusations of research fraud. For most of the next century, the simian tongue and the means for its study existed at the scientific periphery. Both returned to great acclaim only in the early 1980s, after the ethologist Peter Marler and his junior associates Robert Seyfarth and Dorothy Cheney announced that experimental playback showed certain African monkeys to have rudimentarily meaningful, calls.

Charting the scientific conversation about and controversy over the evolution of language from Darwin’s day to our own, Gregory Radick offers in The Simian Tongue the first comprehensive history of a debate whose reverberations shaped modern psychology, anthropology, and other sciences of behavior. Drawing on archives and interviews, Radick reconstructs the remarkable trajectory of this “primate playback experiment” and accounts for its shifts of fortune. Stretching from the 1830s to the 1980s, the book resurrects the largely forgotten debts of the modern behavioral sciences to a Victorian debate about the animal roots of human language.

Called by the Times Literary Supplement a “masterwork in the history of science,” The Simian Tongue reminds us, reviewer Barbara J. King notes, “that science is a spiral staircase; new techniques and theories emerge, not always in linear fashion, from the old. It shows, too, science’s power to shape ways we humans think of, and act towards, our fellow creatures.” For the history behind the techniques at work at the Great Ape Trust, turn to Radick for a thorough primer on the long search for animal language.