Faking Knossos

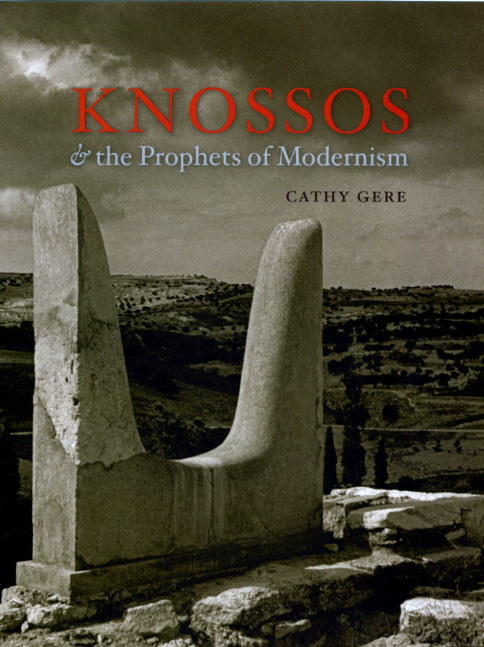

From Freud, to Joyce, to Hilda Doolittle, and Robert Graves, many of the twentieth-century’s most influential artists and intellectuals have, through their work, demonstrated an obsession with the roots of Western culture in ancient Minoan civilization. The source of this phenomenon, as Cathy Gere argues in her new book Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism, can be traced in large part to British archaeologist Arthur Evans’ coetaneous discovery of the palace of Knossos on Crete.

Beginning in the Spring of 1900 Evans engaged in an unprecedented project to not only unearth the ancient Minoan civilization, but to recreate it, commissioning a cadre of artists and architects like Piet de Jong, and Swiss artist Émile Gilliéron to reconstruct the city’s ancient buildings out of reinforced concrete, and piece together sparse fragments of Minoan frescoes with artwork of their own. The result, as Mary Beard notes in her review of Gere’s book for the August New York Review of Books, was a “radical blurring of the boundary between authentic Minoan artifact” and modern fakes.

Yet despite its historical inaccuracies, as Gere shows, Evans’ work gained intense popularity amongst modern interpreters who found in his fanciful reconstruction at Crete, the ancient pagan precedents for their own visions of Western civilization. In her review Beard praises Gere’s work for its insightful demonstration that as much as “twentieth-century culture, from Evans on, projected its own concerns onto Minoan archaeology,” Minoan archaeology conversely influenced twentieth-century culture. And with Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism, we now have a fascinating chronicle of this unprecedented confluence between the ancient and modern worlds—one which continues to shape western culture to the present day.

You can read Beard’s full review at the New York Review of Books website, or read the introduction to the book.