TRAFFIC: W. J. T. Mitchell and Tzvetan Todorov, Part III (Final Installment)

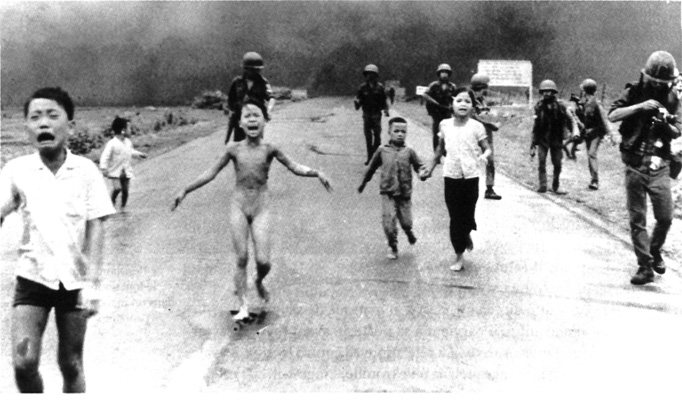

W. J. T. Mitchell (Cloning Terror: The War of Images, 9/11 to the Present) and Tzvetan Todorov (The Fear of Barbarians: Beyond the Clash of Civilizations) finish their discussion, focusing on Nick Ut’s iconic image of the Vietnam War, the duty of humanities scholars, and the changing face of liberal democracies.

**

Dear Tzvetan:

I have located the picture from the October 23rd New York Times, and it is, as you suggested, quite appalling. The little girl, having seen her parents killed in front of her by U.S. soldiers, is wailing in grief, while the figure of a soldier stands in the shadows outside the illuminated area where we see the blood-spattered child. I sometimes wonder how an embedded photographer can bear to take such a picture, which was clearly done at very close range in the immediate aftermath of this event. The picture also raises the question of the ethics of beholding. As James Agee put it so memorably in his commentary on Walker Evans’s photographs of destitute sharecroppers:

“Who are you who will read these words and study these photographs, and through what cause, by what chance and for what purpose, and by what right to you qualify to, and what will you do about it?”

The picture defies commentary of any interpretive sort; it is more like the direct transcription of a trauma in its naked, inconsolable appeal for pity and comfort. What it is doing in conjunction with a news story that tends to minimize U. S. responsibility while engaging in observations about the comparatively greater cruelty of the Iraqis toward their own people is—to me—completely inexplicable and quite shocking. For me, the picture is rather like that image that has become iconic of the Vietnam war—the 1972 photo by Nick Ut of a naked Vietnamese girl, her skin burned by napalm, fleeing from her burning village. I don’t think this image will become iconic in the same way for a variety of reasons, but any American who sees it should, in my view, think long and hard about what has become of the United States. We are supposed to be a beacon of peace and liberty, but instead we have become the greatest purveyor of military violence in the world, with uncounted hundreds of bases scattered around the world, and two major wars in progress with no end in sight. This is not some accident of history, but reflects a fundamental pathology and pattern that can only lead to disaster for our nation. This picture, which is a product of a war fought in the name of every American citizen, should lead all of us to take a long look in the mirror.

Best wishes,

Tom

**

Dear Tom:

I gladly agree with your just remarks on the picture I mentioned earlier. It does remind me more of the Nick Ut photo of the running Vietnamese girl than the tortured prisoners of Abu Ghraib, and the presence of the photographer at that very moment is indeed somewhat problematic: in a way, he has become a part of this terrible event.

I would generalize another remark of yours: I think not only American citizens but also those of the European states should “think long and hard about what have become” our liberal democracies. On the international scene we have adopted a kind of democratic messianism, i.e. the strategy of using military force in order to impose on distant countries the regime we consider most appropriate for them. On the internal front the very notion of common interest, implied by the democratic idea, seems to be fading away. This doesn’t mean that the picture is entirely black, nor that in some distant place flourishes an idyllic utopia. In Europe as in the United States we live in pluralistic societies, by far preferable to China or Saudi Arabia; but in these societies antidemocratic forces have become stronger. I think that we, professionals of the humanities, should accept fully our role as educators, and use our capacities in interpreting—images, words, fictions, ideas—thus contributing to the defense of the values we cherish.

Yours,

Tzvetan