Six Questions for Hollis Clayson, author of Illuminated Paris

To celebrate International Museum Day on May 18th, we sent professor of art history and the Bergen Evans Professor in the Humanities at Northwestern University, Hollis Clayson, a handful of questions about art and the city of light.

Let’s start at the beginning: what sparked your interest in the nighttime illumination of Paris? Was there an artwork, or a trip to the city, that started your research?

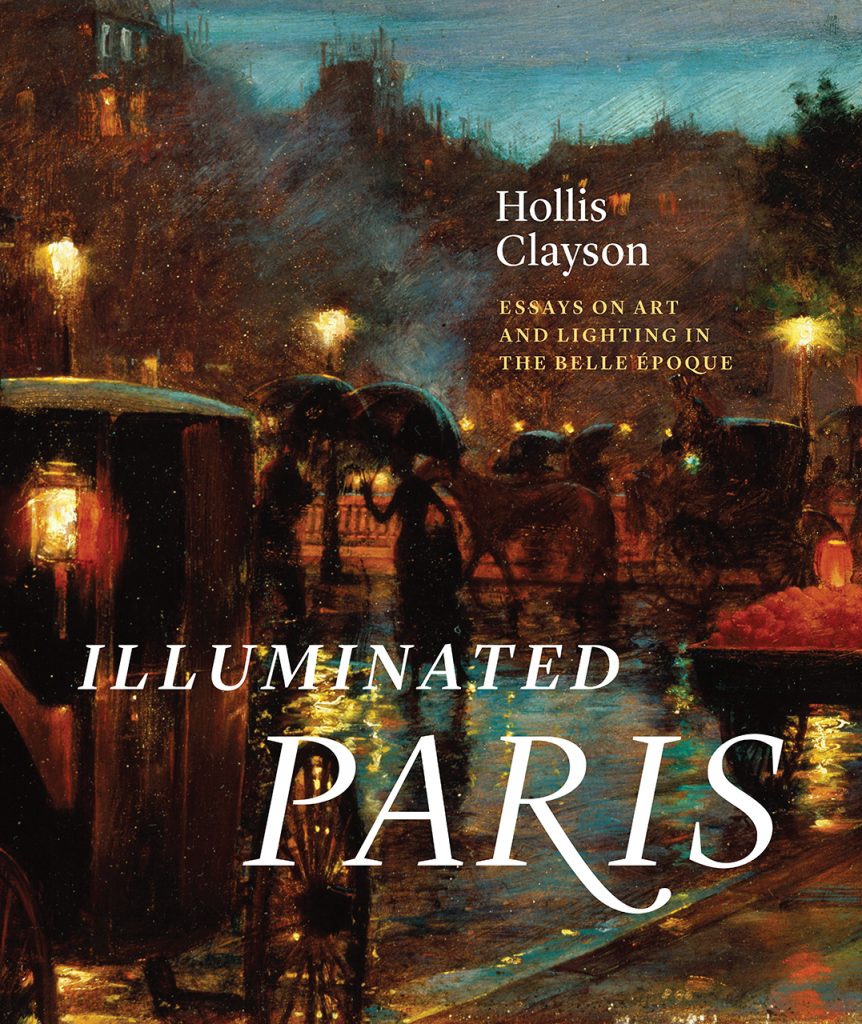

The book grew out of my interest in the topic of Americans especially artists in Paris which of course grew out of my experiences (from wonderful to terrible) as an American in Paris, an American billing herself as an “expert” on French culture. At the beginning of the enterprise, I was initially focused exclusively on Mary Cassatt (who figures prominently in the book and in other essays of mine), but the light angle only really dawned when I saw a painting in storage at the old Terra Foundation Museum of American Art on Michigan Ave., which is on the cover of the book: Charles Courtney Curran, Paris at Night, 1889. It made me start asking questions about the American imagination of the Paris night and how it differed from the conception of the modernity of Paris in the works by the indigenous Parisian modernists. That’s when I coined the term Outsider Nocturne.

In Illuminated Paris, you highlight a selection of artworks as examples of the effects of the movement between gas and electric light in the city. Is there a piece that you find especially fascinating? What does it reveal about changes—artistic, cultural, or social—that have resulted from the evolution of lighting in Paris?

Very early I fell hard for the two Luxembourg Garden canvases (1879) by John Singer Sargent, another American in Paris. The amazing subtlety of the combined light effects in the two pictures (moonrise, twilight, gaslight, a glowing cigarette end, and reflected moon light on the boat basin) got me asking detailed questions about the chronology and technology of lighting innovations in the French capital. I gradually understood that Sargent was both attracted to the park by the new lights closeby (electric arc lights) but referenced them only indirectly in his pictures. That line of inquiry also gave me the chance to deal critically and historically with the changing status of the French capital’s old (metaphorical) nickname, The City of Light.

You discuss how changing technology affects the works of art that are being made and how we experience our world. Are there any technological shifts happening today that you are particularly intrigued by?

I am of course fascinated that the year in which I really got started on the project (2004) was the 125th anniversary of Edison’s incandescent bulb. And that as I brought the book to its conclusion the incandescent bulb was dying alongside one of its upstart ineffective surrogates, the widely maligned compact fluorescent. Now both are overshadowed and being replaced by LEDs, the great electric light source of the 21st century. I am very interested in how LED lighting is transforming art museum interiors. Moreover right now the city of Evanston, IL (where I live) is engaged is a complicated debate over the possible removal of its elegant and restrained Tallmadge streetlights. Indeed, A Street Light Master Plan has been passed by the City Council.

As we see in the book, change comes with both loss and newness. Looking also at another of your books, Paris in Despair, what are some ways that artists have addressed changes in their surroundings, whether those changes are tumultuous, welcomed, catastrophic, or revolutionary?

The most subtle artists, or at least the ones I have admired the most in the modern era, have responded to galvanic change in myriad subtle ways. Denotation and description are often outflanked in their work by indirection, displacement, and disavowal. But then as my last book made clear, I’ve always been more interested in despair than jubilation, and I’ve preferred ambiguity to closure.

So soon after the loss of much of Paris’s iconic Notre Dame, could you speak to the ways that art serves as a record, or preservation, of history? What are some ways that we might approach art works as historical records, and how would you address questions of restoration and preservation when works are damaged?

A very complex question this is. One of the unexpected salutary outcomes of the mourning for the loss of the roof and the steeple of Notre Dame is the lesson that a very wide swath of people have learned about the historicity of the Cathedral: that so much of it was and is a nineteenth-century building rather than a uniformly Gothic one. Does this point to how it should be restored? No, not really, plus Macron has announced an international architectural competition for a brand new 21st-century steeple. Let’s hope it will be as congenial an addition to Notre Dame as I.M. Pei’s Pyramid was to the courtyard of the Louvre.

Finally, since today is International Museum Day, we’d love to hear about some of your own museum experiences. Do you have a favorite moment or memory at a museum? When you walk into a museum or collection, is there a type of image—a quality, subject, or scale—that immediately draws you in?

I didn’t go to an art museum until I was a senior in High School. And I’m still making up for lost time. Students often comment on my “superhuman museum stamina.” I guess I just can’t get enough. My museum tastes are fairly catholic but I am almost always drawn to nineteenth-century canvases and works on paper first and last. That said: the hyper-quirky Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris may be my very favorite. The talking warthog room would be hard to beat.