Reflections on “Young Men and Fire” by James Kincaid

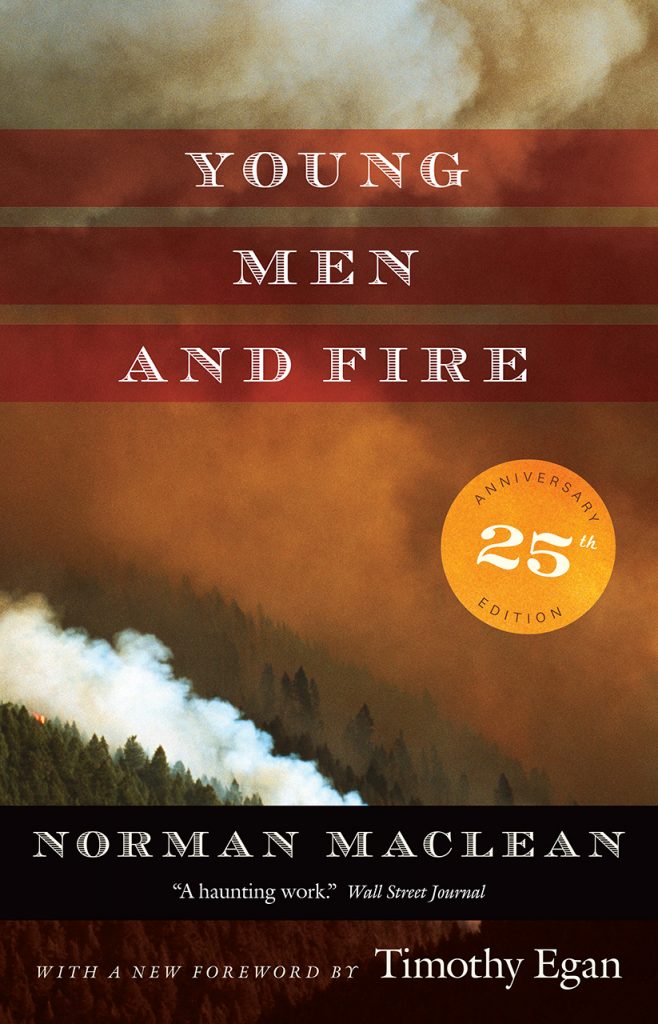

August 5, 2019 marks the 70th anniversary of the Mann Gulch tragedy, when a crew of fifteen of the US Forest Service’s elite airborne firefighters, the Smokejumpers, stepped into the sky above a remote forest fire in the Montana wilderness. Two hours after their jump, all but three of the men were dead or mortally burned. Haunted by these deaths for forty years, Norman Maclean put together the scattered pieces of the Mann Gulch tragedy in his Young Men and Fire, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1992.

In honor of the anniversary, we invited James Kincaid, who reviewed Young Men and Fire for the New York Times Book Review when it was first published, to offer his reflections on the book and its enduring significance.

My first encounter with Mann Gulch came when my raucous, unpredictable editor at the New York Times Book Review called: “Kincaid, got the best thing in years. Homeric, positively Homeric. I’ll send it on if you think you’re up for it. I know you’re not up for it, but you probably think different.”

I don’t know if I thought different, but within a few days, I was there, in my head with Norman Maclean, running with those young men, no more than boys, up the too-steep hill with that roaring blow-up too close behind them, moving too fast. Maclean’s prose is as unrelenting as anything in the language, spare and fierce and sometimes tender: “They were young and did not leave much behind them and need someone to remember them.”

Shortly thereafter, I got to know John Maclean, Norman’s son, who was in the midst of writing about another fire, eerily similar, this one on Storm King Mountain in Colorado. It was a complex undertaking for the younger Maclean, partly because his father had tried desperately to form the Mann Gulch fire into the pattern of a classical tragedy, where the deaths would be somehow sacrificial and full of meaning, not just empty, absurd. Norman Maclean had based much of his reliance on this pattern on the belief that we had learned from the Mann Gulch fire—learned about equipment, technique, and, most of all, blowups.

And here was another blowup a few decades later, swallowing up just as many wildland firefighters and suggesting that any idea that we can “learn” enough about horror to outface it is perhaps noble but also evasive. Fire will always win—and tragedy has no consolation, none.