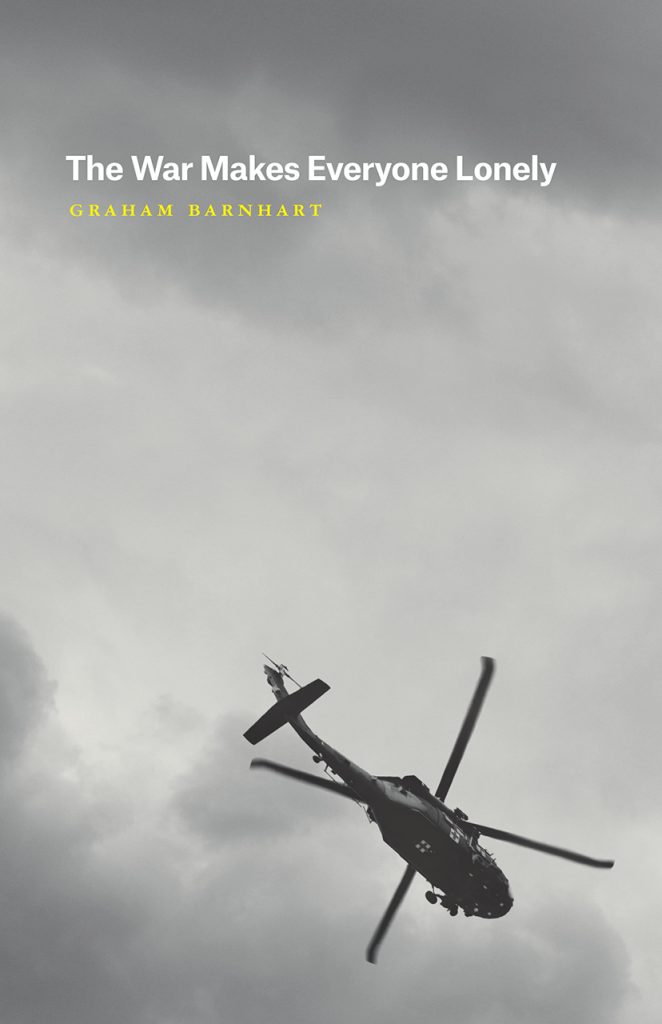

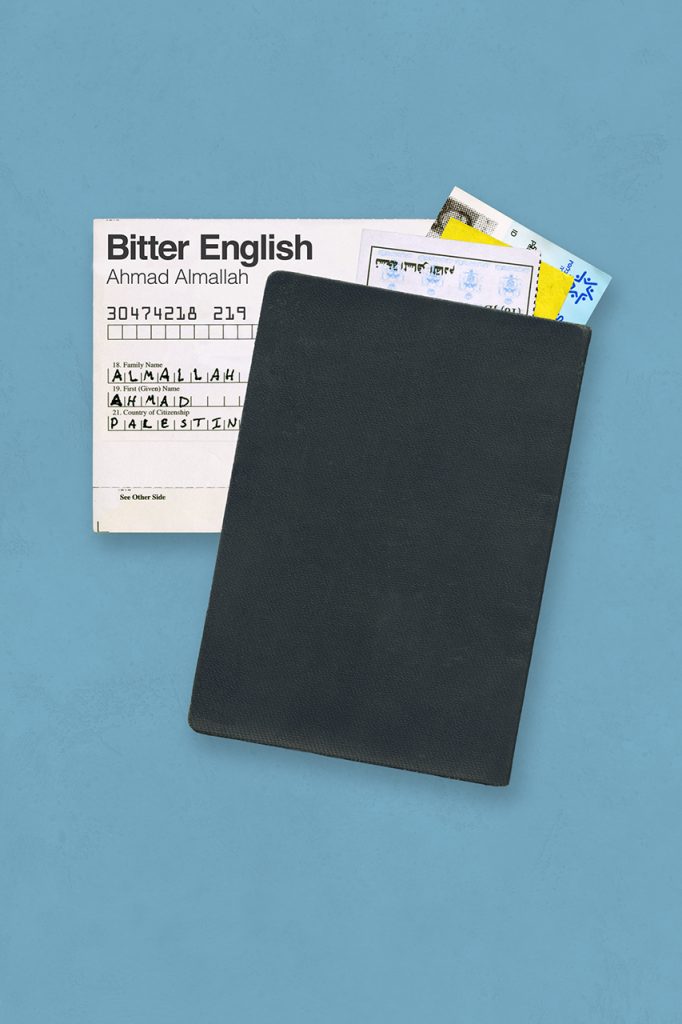

Q & A with Poets Ahmad Almallah and Graham Barnhart

This fall, the Phoenix Poets series features debut collections by two poets: Ahmad Almallah and Graham Barnhart. We spoke with these poets about their new books, the process of writing and assembling their collections, and their experiences of war, central to both of their works.

This fall, each of you will publish your first book of poetry as part of the Phoenix Poets series (congratulations!). Could you both talk a little about your process of organizing your work into a collection and how you decided on the theme and scope for your book?

Graham Barnhart (GB): I started writing these poems while I was in the MFA program at Ohio State. I’d been active duty for six years and just transferred to the national guard, so it was a strange time. I was still in the Army but also kind of not. I didn’t think of the poems as a book until later, but at the time I just followed the stories and experiences that most interested me—that sparked poems. I knew the theme of the book in very general terms would be war and my military experience, but the scope or focus didn’t emerge until I started trying to organize the poems into a manuscript. My first orderings were based on chronological timelines. I wanted to show cycles of training, deployment, and homecoming, but gradually I realized that timeline was how I understood the war but not how I experienced it. So instead I organized the poems in thematic cycles, following isolation, misconceptions, and the ability/inability to communicate experience.

Ahmad Almallah (AA): This is not an exaggeration, but I began working on this book when I decided to put my life on the line for poetry. Before that I thought I could combine an academic career with scribbling a few poems here and there, mostly in Arabic, some in English, but in both languages: bad poems! So in a way, I decided that it is time to exile myself in English—a language I’m not comfortable with. But I took it to an extreme as most people around me saw it: I quit my tenure-track position at Middlebury College and I moved to Philly, only to write. And when I was in Philly after I’ve done that very stupid thing, I had no choice. I had to get up every morning and find a space that will offer me a poem. It took me almost three months after I moved with my wife and daughter to write a poem that’s convincing to me. When I shared that poem with my wife and partner Huda, the relief on her face was my biggest “award” at that time. I say it jokingly now, but she and others around me thought that I was completely nuts before that poem. Then I went on looking for another poem, and another. I never thought that I’m writing a book until I wrote the poem “Bitter English,” and that was two years after our move to Philly, precisely in the summer before I started my MFA at Hunter College. Only then I was able to look back at what I was doing, and I started organizing the poems towards this book. Being at Hunter College among the wonderful poets there was immensely helpful and encouraging. Although I felt at that time that my life was dedicated to commuting from Philly to NYC for the most part, I was reading and writing and organizing on the way constantly. This gave me the time and space to complete it. It was physically taxing but I really miss it!

Both Bitter English and The War Makes Everyone Lonely address the difficulties–linguistic, cultural, and geographic–of life away from one’s homeland. How does writing poetry affect or aid in processing experiences of isolation, trauma, and culture shock?

GB: It’s not a pleasant or comfortable feeling. I think some degree of isolation or separation, of feeling alienated to some extent (from oneself, one’s community)is vital when transmuting experience. Writing poetry about deployments has been a way of seeing myself there, of standing outside the experience, an attempt at a some version of (voluntary/intentional) double consciousness, which is of course profoundly isolating. To see yourself as others see you, even to try, separates one from oneself. To do so by choice is a privilege, of course, but also a moral imperative as a US soldier, an invader and aggressor, writing about that experience.

AA: Essentially I believe that poetry doesn’t help in alleviating the loss or the fact of being uprooted. On the contrary, it works very often to aggravate these feelings, making one feel more and more isolated. Writing is a very lonely and difficult space, and maybe this only applies to me: but if it does not feel that way, then I know I’m not really writing. Probably the time you dedicate to it is the only relief, being lost in the act. But facing the world with it, that’s just a myth, at least that’s how I feel.

GB: I agree with Ahmad here. Aggravating and troubling those feelings is often generative for me as well. The act of writing itself can be soothing, but I’m distrustful of work, especially my own, that offers a cathartic release.

Each of you also discuss war: with you, Ahmad, having left the conflict in Palestine, and you, Graham, as a former member of the US Army. Could you share some of your experiences in writing about these themes of war, estrangement, and the resulting complex relationships to your countries?

GB: Writing about my participation in our wars helped me see my complicity in them. I shouldn’t have needed help, but somehow during my service, I considered myself apart from, among but not of, the army. Paradoxically, I never felt more separate from my country than when I was acting on its behalf. I was a medic, and when I provided medical care, that was me, Graham Barnhart, doing something that seemed good. When a war crime was committed—or any of those acts not labeled a crime by virtue of having occurred in a war zone— say, the Airforce targeted a civilian hospital, killing forty-two people, that wasn’t me. That was the Air Force. That was America. But we all wore the same jerseys and the same flag. We’re all America.

AA: I guess for me, war was my childhood’s background. I have no way to escape it. It creeps in. it’s part of my formation as a person. And as strange as that may sound: remembering that time of war through the poems makes me long for it, for my childhood in it. I only began to realize the traumatic effects of it on me when I stepped out of it. It was definitely not normal, unnatural in the most unnatural of senses. There was a vague terror following you as a child all the time. You did not understand it, you just thought it part of your regular day to day life . . . and that was the most terrifying thing about it. When violence is normalized to the level of the commonplace, then something is really wrong with existence.

GB: Ahmad, your observation is incredibly important. So much war writing by American veterans, by soldiers in general, exoticizes war as a foreign landscape—a place to be visited and returned from. When we privilege the perspective of a voluntary, active participant, we risk essentializing it as the experience of war rather than just one of many.

For instance, in an essentialized male/veteran perspective that sense of longing you identify becomes a romanticization equating danger or proximity to death with clarity and intensity of experience. We see it in depictions of veterans from Rambo to Revolutionary Road’s Frank Wheeler. Do you feel like you explore your sense of longing directly in your poems or is it more of a feeling that fuels them?

AA: What an insightful and sharp point you bring up here Graham! In that sense, I really struggled that the work not be nostalgic in nature, because nostalgia, in my opinion, will give way to exoticization. My attempt was to fuse the two worlds I seem to find myself in-between, just the way I experience them, that is to say, not fully: to bring an absent place to another I physically occupy now and essentially to bring out the inner tensions of these worlds within me into poems. Nostalgia or exoticization make it seem that these two worlds are inherently different from one another. But that’s a flawed formula. It’s our placement/displacement from them that makes these worlds collide inside us. That’s the real stuff of poetry I believe, and that’s where our experience is taken away from us in a way. It will then belong to the poem, to poetry. And here I am openly stating my opposition to this idea that has become the trend in the poetry scene today, that the poem is a platform for expressing an identity or for reinforcing a certain kind of identity. The poem should be in essence the deconstruction of any “perceived” identity.

Who do you imagine your readers might be? Is there a type of response, new knowledge, or shared experience you hope they might take away from your book?

GB: I hope civilian readers find these to be poems. Not just war poems but poems set in the context of war and a country of war. I hope veteran readers see these poems addressing the military culture of permeating violence. I hope they see that violence is more than physical danger, that it doesn’t require combat. They know already, but I hope they see that in this book. I remember watching a Black Hawk Down behind-the-scenes interview with Ewan McGregor. He played an Army Ranger in the movie, and, as preparation for the role, he had gone through some of their training. He was shocked by how much that training focused on killing. It’s easy to forget that. It’s easy for that to become normal when you’re submerged. You don’t go to the dentist in the Army to keep your teeth healthy. You go to the dentist to maintain your eligibility for deployment.

AA: I can steal Marianne Moore’s words as a response to this question and say: I write “in plain American which dogs and cats can read!” But no…I don’t imagine my readers to be dogs and cats, though it would be nice if they could read my poems. A more serious answer would be: after being schooled in academic English throughout my experience in the US—getting a Ph.D. was my way of staying legal here—I was dedicated in Bitter English to purging my language of all that high jargon, to writing and playing with plain American English and slang. I found so much more poetic potential there, and I wanted anyone to be able to experience the poems I’m writing, not only the academics and the critics. And in essence I wanted my poems to have another existence, outside and labels and their circles, but in particular, outside circles of privilege. That being said, I have to note that these practical intentions of poets for their poetry are always doomed to failure…and I guess the more you fail in achieving your ideological goals as poet, the more you’ll be serving your poetry. But to keep it on the positive side: it’s not a bad thing to have good intentions!

What are you reading right now? Are there any upcoming books you’re excited about?

GB: I can’t stop reading Taneum Bambrick’s debut collection Vantage, which won the 2019 APR/Honickman Prize. There might be a little bit of bias there though…we’re engaged, but the judge, Sharon Olds, thinks it’s a pretty damn good book too. I’m also teaching Robin Coste Lewis’ Voyage of The Sable Venus, Shane McCrae’s The Gilded Auction Block and Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic for an online Continuing Studies workshop at Stanford this fall (shameless plug…enrollment is currently open), so I’ve been happily devoting most of my attention to them. It’s going to be a very good year for poetry, and my “excited for” list is getting pretty long: Hard Damage by Aria Aber, Karen Skolfield’s Battle Dress, Kate Gaskin’s Forever War, A Nail The Evening Hangs On by Monica Sok, and Carolyn Forché’s new collection, In The Lateness of the World, which I think comes out this March, are all at the top, and of course Bitter English Ahmad Almallah.

AA: I have to say that I don’t read much contemporary poetry, and that’s probably why I feel like an outsider to the poetry scene, not entirely able to comprehend what is going on–maybe that’s also how the contemporary world of poetry feels about me: I only have a few published poems here and there. This is why I’m immensely grateful to the University of Chicago Press for putting more of my poems out there and publishing Bitter English. I don’t know: maybe I should put down the novel I’m reading now, which happens to be Moby-Dick, and maybe I should stop going back to the poems of Emily Dickinson, Hart Crane, Gwendolyn Brooks, and my two absolute favorites: George Oppen and Zbigneiw Herbert. I also constantly go back to classical Arabic poetry and the Diwans of Abu Tammam and Abu Nuwas. It sounds like a pretentious list, but oh my god it’s out of this world, and that’s what I love about it so much. But I confess that I should challenge myself to read more contemporary stuff, and the list that Graham provided sounds wonderful, and I’m very much excited about reading his book. It has the arch of a long and layered poem, which is also what I aimed for in organizing Bitter English.

Do you have any questions for each other?

GB: Ahmad, can I ask more about your decision to give up that tenure-track job and focus on poetry? Is it accurate to say the act of writing, rather than a specific project or goal, motivated your decision? And were you envisioning a career as a poet when you made that move or just, more purely, a writing life?

Also, in the title poem of your collection, you write “that I find this English tongue I use day after day/

boring, in construction, even in poetry,…” I love this statement. To un-boring language seems like a primary pursuit of poetry necessitated by the fact that we, poets, find it somewhat boring in the first place. Usually, I think of this in terms of a commonplace, everyday use of language to communicate rather than the relative boringness of a specific language’s mechanics, construction, and sound. Can you say more about your process writing in English—how you manage to find a sense of intensity in it for yourself?

AA: There was certainly no specific project in mind when I decided to quit my job. The plan was to write, and when people asked about what I plan to do after moving to Philly, I precisely said that: I want to write. Maybe I wanted the writing to come out of a certain urgency, or to put the writing life at the center of my own existence. I felt the effects of that on my writing right away. There was a constant anxiousness surrounding the process and the pursuit of the poem that I never felt before. And that intensity of experience gave way to an intensity of language, or to experiencing language as though my life depended on it and not just as another boring detail in the day to day life. But the thought of seeking a career as a poet never crossed my mind then. On the contrary, at that time I wanted to get my ear tuned to an English that exists outside of institutions and the world of academia. But unfortunately that space for writers and poets outside academic institutions, especially in the US, is getting narrower and narrower, and I see the appeal of writing programs and MFAs for poets and writers as a safe space. Consequently, the role of the poet and the poetry scene is getting more and more “professionalized” and now “digitalized”/”digitized” to a suffocating degree. Not to forget, that it is becoming more and more limited to certain class of people that own the technology and resources to submit their work to contests and journals…etc. And we should remember that the diversity we seek today in the world of poetry is only reflective of that class. In that sense, it’s only decorative, only serving the institutions and journals that represent them, and not necessarily the causes of the people these journals showcase rather than adopt or promote.

Graham, here is my main questions to you: reading your book, I couldn’t help but feel that I am on the receiving end of many of the experiences you were forming into poems. You’ve captured the distance that the military experience constructs between you, as part of the military, and “the other” who by default is supposed to be “the enemy.” In all of this, you captured the horror of the experience within you, and have done so in beautiful poetic terms. But can that be enough? Do you see yourself coming back to this experience and examining it further? And finally: how do you see the poems speaking to people outside of the US, or people who might be on the receiving end of the violence done by the military?

GB: These are urgent questions, Ahmad. Thank you. In short, no, I don’t think that can be enough. I hope the poems can help to locate what is human and what happens to that humanity when it confronts systems of violence. I also feel a responsibility to talk about the military in a new way, to complicate the tradition somehow. My perspective on those systems is complicated, of course, by my participation in them, and in one way or another, I think I will be writing about that for the rest of my life. Going forward I’m interested in addressing that complicity, in addressing the way these violences affect the relationship between humanity and the environment. The ways in which the life or death stakes of warfare subordinate landscape, and allow us to see it as expendable, a lesser casualty.

Bitter English and War Makes Everyone Lonely are both available now. Find them at your local bookstore on our website.