Can We Fill Our Empty Streets?: Brian Ladd on the Role of Streets in City Life

With social distancing protocols in place and many businesses temporarily closed, the current pandemic has drastically changed the public lives of our cities. Eerie videos of cities like New York show a world with fewer cars, cyclists, and pedestrians, while many of us wonder how and when public interactions might resume. Brian Ladd, author of The Streets of Europe, considers not only our current state of lockdown, but also the history and future of city streets, looking at the ways they have changed from pedestrian hubs to high-speed thoroughfares and how we might reconsider their role in city life.

In our coronavirus quarantines, many of us miss not only particular people, but also people in general. Pictures of empty streets remind us that we cannot, like the French poet Charles Baudelaire, “melt into the crowd” to “take a bath of multitude” with its “feverish ecstasies.” Will our current feelings of deprivation renew an enthusiasm for the daily throng? Only if we don’t succumb to fear of city life.

This pandemic does make it easy to believe that the proximity of other people is primarily a threat. When will it be safe to gather in public again? Never, say pundits who have long preached against city life. Life in dense cities, they tell us, is unhealthy, unnatural, and uneconomic. But we should recognize that they are appealing to a visceral revulsion at the proximity of strange and odiferous bodies in buses and streets.

City life revolves around human contact. People carry germs, but they also bring excitement and opportunity. Remember the predictions of doom for New York after the 2001 attacks? What followed instead was an unprecedented boom. People and businesses saw the advantages of diverse populations, pools of talent, and face-to-face interactions. Although urban revival is a worldwide development, it has been particularly striking in the United States, where ambitious young people feel more comfortable in city streets than their parents did, and where they take pleasure in wide circles of acquaintance and even in churning crowds of strangers.

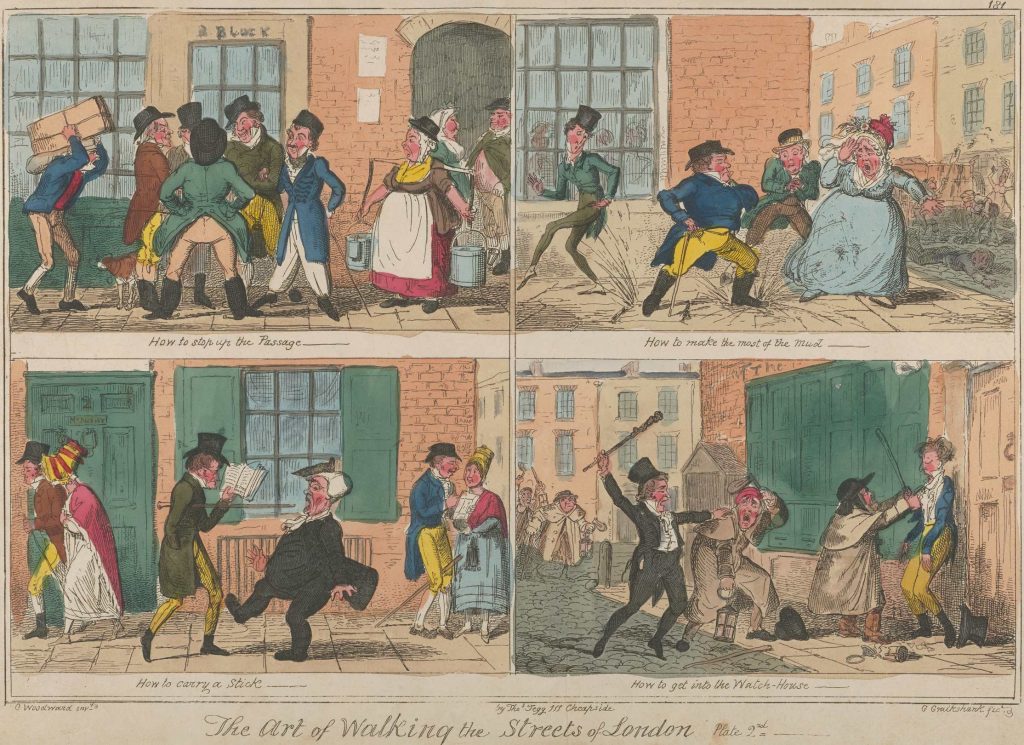

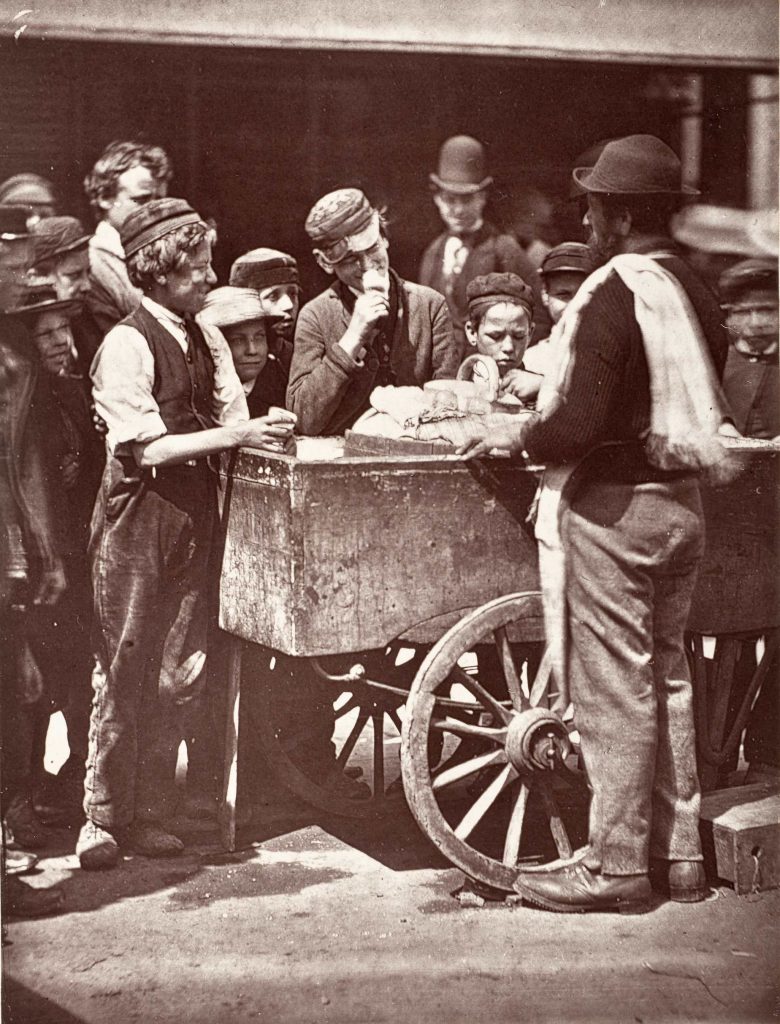

City life has always meant danger and opportunity. “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life,” declared Samuel Johnson in 1777. A few years later, Charles Lamb professed “the impossibility of being dull in Fleet Street,” with its crowds, bookstalls, pantomimes, “steams of soups from kitchens,” and even “the very dirt and mud.” Their metropolis teemed with disease along with street vendors, coffeehouse debates, enterprising strivers, and rich and poor alike strutting out to “see and be seen”—already an established phrase in multiple languages.

Cities, of course, have since been transformed. Long before this pandemic, we were used to seeing empty streets—empty, that is, except for people encased in their motorized steel boxes. Attitudes, policies, and design for the past century pushed our shopping, strolling, and conversation indoors. Outside of a few old and large cities, Americans rarely walk to a destination, except from the parking lot, so few of us experience the pleasures of the street in our daily lives. We have had to travel to a major urban hub to find a street crowd—and now we don’t even have that choice.

This transformation began in the 1800s, when the absence of sewer and water systems, along with ignorance about contagion, left fast-growing European and American cities exceptionally vulnerable to infectious diseases. Steamships and railroads carried waves of cholera and sudden death. Reformers denounced streets packed with hawkers and idlers. Their ideal street was a sterile corridor for rapid transportation, and the arrival of the automobile helped turn it into reality. Pedestrians, now labeled jaywalkers, were shooed out of the way, and streets became places to drive cars.

This suburban model shaped street planning through the twentieth century, even though sanitary improvements made cities measurably healthier places than the countryside by the early 1900s. Today’s cities can claim several additional health advantages, starting with the best-equipped hospitals. The human contact in cities promotes social capital and well-being, which has proven links to better health, most dramatically in reducing suicides and other deaths of despair. City-dwellers also drive less, which means a more active lifestyle and fewer traffic deaths.

A global crossroads like New York may have been particularly susceptible to the initial spread of the coronavirus, but it was an illusion to think that more dispersed populations were safe. Today’s suburban and rural economies are connected to the wider world. Viruses follow wherever people go, and people everywhere want to congregate. Suburban supermarkets, village shops, churches, and factories are proving just as capable of spreading disease as streets and subways.

Caution is warranted. Fear and abandonment of cities is not. Old customs, along with new ones, will help us adapt to new dangers. Perhaps, like some elegant 17th-century European women, we will again see masks as fashion accessories. We also make space for people by reclaiming streets from automobiles, now that car traffic is down and extra room is needed for social distancing. Many cities have temporarily turned car lanes into widened pedestrian walkways. A taste of car-free street life might build support for making these changes permanent.

While remaining cautious, we can take this time to remember the joys and rewards of urban life. We must come to terms with the basic fact that human interaction is both a danger and a blessing.

Brian Ladd is an independent historian who received his Ph.D. from Yale University. He has taught history at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and is a research associate in the history department at the University of Albany, State University of New York. His books include The Streets of Europe: The Sights, Sounds, and Smells that Shaped its Great Cities, Autophobia: Love and Hate in the Automotive Age, and The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape.

The Streets of Europe: The Sights, Sounds, and Smells that Shaped its Great Cities will publish this September. It’s available for pre-order on our website or from your favorite bookseller.