“One of the Fine Arts” by Roger Grenier

“One of the Fine Arts” by Roger Grenier, from A Box of Photographs (2013, translated by Alice Kaplan)

After the war, the street photographers came back to the city. On the boulevard Saint-Michel, like just about everywhere in the world, they took pictures of the passers-by and handed them a ticket. If you wanted to, you could return later, show your ticket, and pick up your portrait on the front of a postcard. Every time it happened to me, I thought about Panaït Istrati, the Romanian vagabond whose stories I loved for their savage hymns to freedom. He practiced his art in Nice, on the Promenade des Anglais.

I had a new camera. To replace the Voigtländer, I bought an old Rolleicord on sale (actually, my mother bought it when someone came into her shop and offered to sell it). So I remained faithful to the model of the poor man’s Rollei. But I’d become a journalist and little did I know that my job would force me to give up photography for years, because of union regulations. Reporters were not allowed to take photos. We used to travel as a team: a reporter, a photographer, and a chauffeur. Thomas De Quincy, a great fan of popular crime stories and author of the celebrated work On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts, notes that “two imbeciles, one murderer and one murdered,” never produced anything of interest. So if you add two other imbeciles, the reporter and the photographer. . . . But it is true that the demon of art can come and tickle even the crudest photojournalists. For this reason, I am fascinated by the case of Weegee [Arthur Fellig].

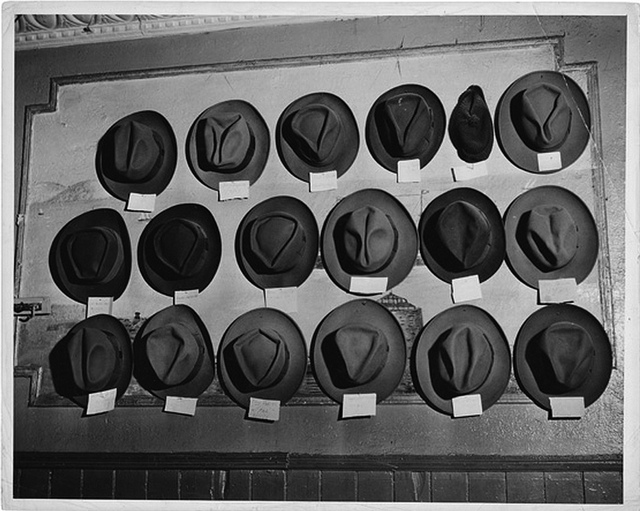

Night after night, Weegee, a New Yorker, took the same atrocious photograph. Always a murdered gangster, always a hat on the sidewalk at his side. This stage of his career lasted from 1935 to 1945.

“One good murder a night, with a fire and a hold-up thrown in, kept me in blintzes, knishes, and hot pastrami, with the nice feeling of folding money in my pocket.”

Weegee practically lived at the Manhattan Police Headquarters, and when he could afford a car, he was authorized to tune his radio to the police frequency. For him, crime was as reliable as a train schedule. From midnight to 1:00 a.m., peeping toms on the rooftops. From 1:00 a.m. to 2:00, stick-ups of the still-open delicatessens. From 2:00 to 3:00, auto accidents and fires. At 4:00 a.m., fights in the bars at closing time, followed by burglaries and the smashing of store windows. After 5:00 a.m. it was time for the people who’d been up all night agonizing to take a dive out the window. But even a brute like Weegee needed a modicum of staging, and his crude Speed Graphic, with its plates and its flashbulbs, was imbued with artistic aspirations. Before taking a photo of a couple of young murderers in prison, he asked the warden to tell the girl to fix her hair and put on makeup: “The papers like their murderesses pretty and wholesome.” About the gangsters struck down on the New York sidewalk that were his daily bread, Weegee confessed, “Sometimes I even used Rembrandt-style lighting, not letting too much blood show.”

Rembrandt-style lighting!

Reading Weegee’s memoirs, you sense he’s not far from thinking that no one has the right to kill, or be killed, without his permission. The shutterbug comes to the conclusion that he is Destiny: “My camera seemed to be deadly as far as the gangsters were concerned. Once I had photographed them alive I always had to pay a return trip to photograph them when they were finally bumped off. They usually landed in the gutter, face up, in their black suits, shiny patent leather shoes, and pearl gray hats . . . dressed to kill. No bumping off was official until I arrived to take the last photo, and I tried to make their last photo a real work of art.”

It would be wrong to think of Weegee as only a crime-scene hack. Crimes were not the only things he photographed. And in any case, he turned out to be a hugely talented photographer. Often he didn’t photograph an event, but the people watching it. he reminds us that just like him—perhaps even more so—we are voyeurs.

Weegee’s colleague Alfred Eisenstaedt had no fewer than ninety-two covers for Life Magazine to his credit. He was born in Germany in 1898 and lived there until 1935. He photographed Marlene Dietrich with Leni Riefenstahl at a ball in Berlin in 1929. This was before the arrival of the Nazis. Also in Berlin, in 1932, he photographed a sixteen-year-old violinist named Yehudi Menuhin. Bruno Walter was with the young prodigy. Soon they were all forced to flee. On June 13, 1934, he was in Venice, where he managed to capture Mussolini shaking hands with Hitler, not yet the Führer, since the elderly Hindenberg was still alive. In September 1933, in a hotel garden in Geneva, Eisenstaedt took the two photographs I find most powerful; the occasion was a session of the League of Nations. Goebbels, sitting on a garden bench, is flashing an enormous smile at someone we can’t see. Suddenly, he realizes a photographer is watching, and in the second picture, his face fills with hatred. Eisenstaedt explained in his commentary, “When I have a camera in my hand, I know no fear.”

In the 1960s, Eisenstaedt came to Paris, accompanied by an interpreter. Every time he got ready to take a photo, the interpreter would say, “Cartier-Bresson already took that one; Capa took the same shot; Brassaï got that one. . . .”

What French ancestor of Weegee photographed the anarchist Jules Bonnot on a marble slab at the morgue? A fat man with a mustache, wearing a worker’s apron and cap, lifts up the famous head to face the lens.*

*Translator’s note: Jules Bonnot, an infamous French anarchist whose “Bande à Bonnot” was responsible for numerous hold-ups and murders, died in 1912 from gunshot wounds in a police ambush.

***

Read more about Roger Grenier’s A Box of Photographs here.